HANNAH SMITH treks off to Leeds in search of the Masters of 3D...

HANNAH SMITH treks off to Leeds in search of the Masters of 3D...

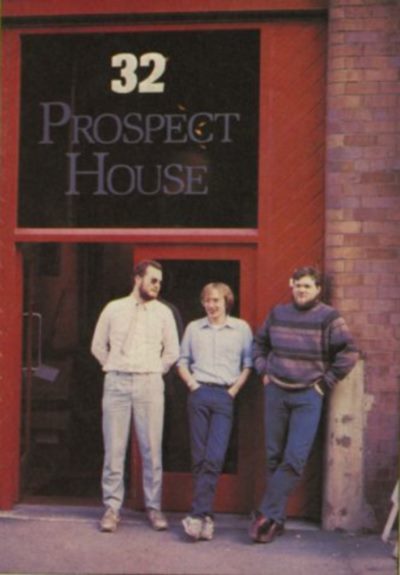

Our visit to REALTIME GAMES SOFTWARE coincided nicely with their second anniversary. Realtime was born on May 8th 1984 in the middle of the founding members’ Final Examinations at Leeds University. From that slightly unlikely beginning, the company formed by Ian Oliver, Andrew Onions and Graeme Baird has gone on to become the market leader in the field of 3D games on the Spectrum.

Working from an office a few minutes walk from Leeds City Centre, the triumvirate were taking a breather when we arrived, having just launched their third Spectrum game, STARSTRIKE II. Not that the central heating boiler nestling in an anteroom to the programming chamber exactly encourages breathers — the temperature in the Realtime room usually approaches that of a Turkish Bath, and it wasn’t long before I began to regret putting on my Ludlow Vest before setting out that morning.

The trio formed at Leeds University — probably at the college bar, rather in a lecture room on the Computer Science course they were following. They soon came to the decision that they didn’t want to work for anyone else after graduating, but had a fairly strong idea that wherever their future lay it was together, and roughly in the direction of computer games.

Tank Duel was their first release and Realtime burst into existence, earning their first CRASH review in the August 1984 issue. Well, they weren’t called Realtime at the time of the launch — in fact they weren’t called anything in particular so vague were their plans. In true student style, Tank Duel was actually completed while Ian, Andrew, and Graeme were sitting their Finals at university. It was written because it was a project that they were interested in, and was sparked off by their healthy interest in the development of three dimensional games.

3D Tank Duel was previewed at the ZX Microfair in April 1984 and was soon pronounced by those in the know as a superior version of the Battle Zone clones which started with Artic’s 3D Combat Zone and continued with Crystal’s Rommel’s Revenge. It was certainly the fastest and most colourful 3D game on the Spectrum, at a time when 3D games in general were fairly thin on the ground.

Realtime’s studenty approach to work is still very evident in their company philosophy. Driven by enthusiasm rather than accountant’s margins, it is almost as if the games they write are ultimately produced for their own entertainment, although Starstrike and the sequel, Starstrike 2 were more of a commercial venture than Tank Duel ever was.

Eight months after Tank Duel, Realtime’s Starstrike heralded a new generation of wire-frame 3D games for the Spectrum. With its fast-moving action and colourful graphics the game was state of the art and, predictably, a success. The team won their first CRASH Smash in December 1984. By then, Realtime’s future in the computer games market looked promising...

It was low profile time on the Realtime front after the release of Starstrike. The trio were spotted from time to time, beer mugs in hand, at a variety of computer shows but little news about their next game was available. They were not basking in well-earned glory or lounging around their Leeds-based office. Well, not all of the time anyway. Plans were already being made for Starstrike 2. Not wishing to appear rude, I did hint that that their third Spectrum game was just a teeny bit late in coming onto the market: it was soon pointed out that very few people realise just how many hard sums and hours of work lie behind the routines that set such complicated 3D shapes spinning and whirling on the Spectrum screen. Each level of the game is so different to the preceding one that every section was like a separate game to write. “People tend to look at games simply as pretty colours and clever graphics,” complained Graeme as we all stumbled out of an Italian restaurant, blinking like moles at the sudden change in light. Back at base, a flow chart on the office wall was called upon to support the argument. A quick glimpse of the convoluted inter-relationships between the sections of the game was enough to dispel any doubts about the complexity of the programming that lies behind it. “We’re also very lazy,” added Graeme, his tongue very firmly in his cheek.

Realtime were one of the first software houses to emerge onto the market, yet they have decided to remain small. To date they have only produced three games for the Spectrum. Had they not been tempted to become a facilities house along the lines of Denton Designs who produce games to contract, for others to publish? Definitely not, said Andrew Onions. Realtime are involved in some conversion work at the moment — for themselves.

Filed under E in their filing cabinet, lurks an Enterprise. A while ago, they agreed to convert games to run on this machine, quoting a price and a three week turnaround. After a slow start, they managed to crack the three week deadline, and are now capable of knocking the bulk of an Enterprise conversion out in a few days, spending a week on the music to round the project off. Getting paid has proved a little problematic, and all three now adamantly insist that this line of work is not one they are keen to pursue. The Enterprise is about to be moved to the drawer headed T in the cabinet — they’ve found it makes an excellent tray, and it’s more often seen in the corridor, keyboard side down, supporting three cuppas on their way to the programming zone.

It’s going to be in-house conversions from now on — work had just started on the Amstrad version of Starstrike 2, and we were treated to a demo screen or two. Amstrad owners should be in for a treat any day now.

All their success with 3D games on the Spectrum has not been without its pitfalls. Being such a small company in the modern, commercialised computer games world has its handicaps. Certain large chain stores are only now accepting Starstrike II on their shelves having refused to handle its predecessor. And a few hairy financial moments were experienced before its release, when large sums of money had been committed to advertising, leaving very little cash to live on while the game was finished off. Student experience was undeniably an asset during confrontations with Mr. Bank Manager at this stage.

So far, all Realtime’s Spectrum games have been in 3D. I tried to prise the conversation away from drunken student parties and general crazy, wacky student stunts to find out why this was. “It’s mainly Graeme’s idea,” said Andrew, carefully deflecting the question to another part of the room. It’s clear that 3D games represent a challenge to the trio — they seek to improve their mastery of the techniques involved with each subsequent release.

“When we start writing a game we tend to go out and buy copies of similar games that are available, so we can see what the competition is like. Then we try to think of ways we can improve on what’s already on the market,” Andrew had told me earlier over a seafood pancake. Certainly Starstrike II is more adventurous than any other 3D game currently on release. But how much further forward can 3D games realistically go? The stage is fast being reached where to get just a tiny improvement on the 3D display, a vast amount of additional memory is required. It’s become a straight play-off between speed and memory space.

Has the point been reached where 3D games can go no further? Nobody knew, but it seemed likely, they agreed. I got the feeling, however, that if I’d have asked them the same question just after Tank Duel had been written I may have got a similar answer. When it comes to reaching the limits on 3D Spectrum games, Realtime have stubbornly insisted on proving everybody wrong. So what plans are afoot for future Realtime games? All answers to this question were tactfully avoided so I bided my time and approached the subject two bottles of wine later.

Realtime hasch, sorry, has, two games in the planning. One of these will be three dimensional and should develop gameplay more. Lots of hard thinking lies ahead. The scenario is likely to involve a lead character marooned on a planet who has to collect various objects in order to find a way off. This will undoubtably all change in the fullness of time — maybe a CRASH preview will help the process along: we got things a little mixed up in the piece previewing the first Starstrike, but the team played along...

The workload behind Realtime, like the equity, is split equally between Andrew, Graeme and Ian in true co-operative fashion although Graeme and Ian tend to stick to the programming side of things leaving Andrew Onions to handle the businessy bits. This invariably leads to mock arguments between the three. Ian and Graeme criticise Andrew’s commercial exploits, while generally leaving him to get on with it. If he gets thing right, praise is not forthcoming. They all have personal specialities although none of these extend to screen and inlay artwork. Andrew Onions, for instance, specialises in what he describes as the ‘twiddly bits’: sprites and that sort of thing.

One of the main reasons why the games take so long to produce is because a lot of time is spent hanging around waiting for each member of the team to finish his own individual section, so that the game can eventually be pulled together. The screen graphics side of things is being more strongly developed at the moment and there is the possibility that a fourth, artistically inclined person may be hired.

So, what of plans for a Starstrike III to complete a trilogy? (everyone else seems to be doing trilogies.) Reaction to this question was met with a variety of adamant denials and “well ... I don’t know’s”. The general consensus of opinion was that a follow up to Starstrike II was highly unlikely — although the Starstrike games have been very successful, the 3D Masters are not overly keen to do a repeat performance and are generally sick of the sight of them. But then again... As usual, nothing definite was divulged.

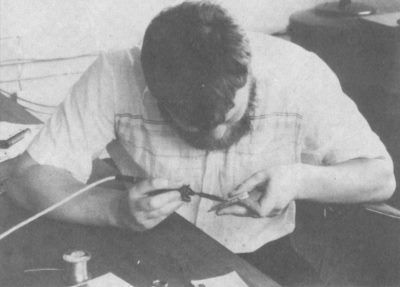

Ian Oliver wrestles with soldering iron and edge connector, to fix a Kempston/128 bug

Although Realtime is predominantly a software company, they do dabble in the hardware side of things. While we were at their office we witnessed Ian Oliver doing barbaric things with a soldering iron. He was trying to solve a problem. A while ago, he came up with a wizard programming wheeze, that allows programmers to take advantage of a quirk in the 48K Spectrum’s make up to speed up certain bits of code. Being a generous fellow, he passed his tip around the computer industry, and lots of programmers used it. When Sinclair made the 128K Spectrum, they changed its internals round a bit; and now 48K programs that exploit this little programming wrinkle won’t run in 48K mode on the 128 if a Kempston interface is in action. (A full explanation of the problem appears in this month’s TECH TIPS.) Ian’s confident he can kludge the 128K Spectrum with a handful of resistors soldered onto the edge connector, but he didn’t have a lot of luck while we watching him.

And so it was time to wend our merry way back to Ludlow through the spectacular scenery of West Yorkhire. Realtime are undoubtably the best when it comes to writing 3D Spectrum games and as we pottered back towards Shropshire I was left wondering what their next release would really be. Would there be a Starstrike III after all or would the next game from Realtime incorporate the cunning vertical scrolling we had previewed on a beat-up black and white monitor that day? Perhaps there’ll be a 128K version of Starstrike II... They could certainly make use of the extra memory.

Andrew Onions, Ian Oliver and Graeme Baird are sensible fellows. They didn’t want to bother themselves with answering boring questions about the Software Industry. They were far more enthusiastic to relate the rip-snorting stories of their student days, and tease Ian about losing an argument with a dry stone wall in the company car — he still had the black eyes to prove he lost. In their position, I think I would have been too.