With titles like Crash and Zzap 64, Newsfield changed our view of video gaming magazines forever. Employee Matthew Uffindell was there from the very beginning to the bitter end, and reveals the inside story on this revered publisher.

With titles like Crash and Zzap 64, Newsfield changed our view of video gaming magazines forever. Employee Matthew Uffindell was there from the very beginning to the bitter end, and reveals the inside story on this revered publisher.

This article was originally published in Retro Gamer magazine issue two, now out of print. It is reproduced here by kind permission of the author, Matthew Uffindell, and of the Retro Gamer management at the time.

I was reading through Your Computer in 1983 when I stumbled across a half-page mono advert for a mail order company called Newsfield that was selling Spectrum games out of a residential address close to were I lived. Intrigued by the fact that a software mail order firm has been set up in a small rural town such as Ludlow, I quickly realised it was the perfect opportunity for me to easily expand my budding games collection. So I decided to pay them a visit.

From the moment I knocked on the door my life was transformed — which at the age of 17 was no mean feat. Roger Kean invited me in and introduced me to Oliver Frey and his brother Franco Frey. I had an enormous interest in the games industry, frequently visiting arcades to play on the latest games, and the three of them quickly cottoned on to my enthusiasm and offered me a job in mail order despatch.

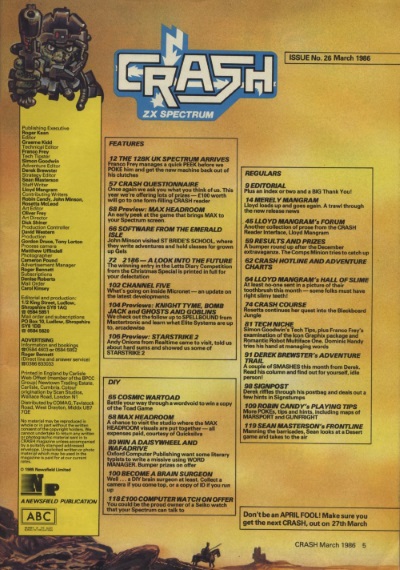

It wasn’t long afterwards that I started reviewing games for the catalogue sent out with every order. The catalogue was such a success that WH Smiths was approached with an idea of a games review magazine for the Spectrum. They thought that it was a unique idea and Crash was born a few months later, produced on a shoestring budget. It was an instant success. The content was different from that of the other magazines of the time, which mainly concentrated on program listings that needed typing in.

Reviews in Crash were detailed, unbiased and written by three people — Roger Kean, myself and the legendary Lloyd Mangram. Lloyd was a character, well, sort of. A little, if at all known fact was that he never existed! Lloyd’s input was the joint combination of text and opinion from both Roger and myself. I don’t think anyone else has ever admitted to that before.

Roger and I worked in an area smaller than your average bathroom. A rented TV, a 16K Spectrum with the dreaded 32K RAM pack, and a typewriter were all the two of us had, and from that room hundreds of games were play tested, reviewed and photographed. I would dictate a review to Roger while playing the game and he would tap eagerly away at his typewriter, then play the game himself for a while before committing his views to paper. The afternoons were still dedicated to mail order fulfilment, something that became a mammoth task because Crash was in effect a huge catalogue for the mail order side of the business. As the magazine grew, so did our mail order commitment.

After a while Chris Passey, another reviewer, joined us. He used to take away a batch of games, play them to death and return with rough cut reviews about a week later. His reviews supplemented Roger’s, ‘Lloyd’s’ and mine, so between us there was never any problem in producing the now standard three views per game.

In the meantime, Oliver Frey created the most amazing cover illustrations for Crash. They were totally different from anything else in the marketplace and inspired by a major game release or the lead topic in each issue. It took several days to complete a cover illustration which would start as a rough pencil outline gradually built up with solid inks and airbrushing. It was like watching an old master at work. Each of us would occasionally give him input into where we thought an improvement could be made. Sometimes Oliver accepted the comment and implemented the idea, other times he would bluntly tell you to go away. Creative geniuses are like that so we accepted it.

Oliver’s covers, our software reviews and previews, Franco Frey’s hardware reviews (Oliver’s brother was a techno-whiz who eventually went on to design a brilliantly simple joystick interface called the ComCom), and regular hints and tips meant that Crash quickly developed into a market leader. At its height it had a circulation in excess of 100,000 copies per month — something that was unheard of at the time for a single platform magazine.

As things grew we became more professional and so did the magazine. I remember when my first kit upgrade arrived. It was a Microvitec Cub and only came in for a hardware review, but never got returned. This transformed the screenshots from fuzzy unsaturated stills to what was then stable, sharp and vibrant colour. It was a visual pleasure while playing games.

It's January 1984 and you've got a pound note in your pocket. Which Spectrum magazine do you go for? Sinclair User is still banging on about the ZX81 and has a bearded rock climber on the cover. Your Spectrum is talking about keyboard buffers and chess tournaments. And then there’s Crash, with an arcade-loving alien on the front and the promise of over 400 game reviews inside. It wasn't a difficult choice back then.

Software Houses quickly realised that a good review in Crash helped them to sell loads of games, even more when a title was awarded a 90% plus rating, earning it Crash Smash status.

This became a point of power in some respects. Software companies pleaded for a Smash award, giving us beta games for trial reviews. If we didn’t award a game a Smash they would ask us how they could change their games in order to get one. Ruthless and unbiased was the only way we knew though. If a game was rubbish we would look the programmers in the eye and say so. They knew we couldn’t be bought and because of this, we gained total industry respect.

The power of reviews could be seen in the shops where huge chains refused to stock games unless they had prior knowledge that it would be a Crash Smash. The team could make or break a business just by writing a rave or damning review.

Many smashes were previewed successfully in beta stages. Programmers would bring in monster computer development systems all racked up so that they could see our reactions to their latest creation. Crystal’s Dark Star was presented in this way. It so blindingly quick — it just had to be seen to be believed. (For the record I always thought that Realtime’s Starstrike had the edge and was more playable but I might have been biased as it was co-designed by a former Ludlovian chap.)

We developed a special relationship with quite a few companies, including Ultimate. No other magazine managed to get anywhere near as close to them. Ultimate were at the pinnacle of programming Spectrum hardware. We always managed to get the latest piece of software before anyone else. The major benefit of a small team was that we were able to react exceptionally quickly to new releases and often took the review of a game up to the print deadline.

After several months of writing in what was effectively a cupboard, it was decided that more space was required. An office building in the centre of town became available. This was leased, and carpets were laid in various rooms.

By this time, the number of staff had increased to a heady six. Denise Robert had been employed in the early part of the year to take over my duties on the software side of the business, leaving me free to concentrate on reviews. David Western was taken on to lay out the magazine (which was done with galleys for text, cut up and pasted onto layout sheets) and improve the screen shots which appeared in the magazine. This freed up Roger from that side of the business.

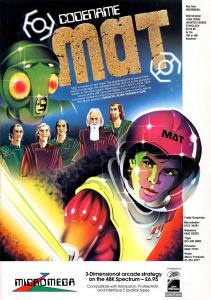

The rumour is true. Codename Mat really was named after Matthew!

For me, Micromega’s Derek Brewster produced perhaps the most memorable beta game. I remember him paying us a visit from Newcastle. He silently loaded his then untitled game and I watched amazed. The 3D graphics were fantastic for the day, with great game play. I remember taking it home with me in the evening and playing it through the night. I raved about it. Derek must quickly have realised how important my opinion was to the success of this game as from that point onwards it was called Codename Mat.

Unbeknown to me, Roger, Oli and Franco had decided to turn one of the rooms into a photographic darkroom where mono screen shots could be turned into halftones (converted into dots for printing). Aware that I had a keen interest in photography they asked if I would like to do the honours, which of course I did.

It was nice to finally have some space. Roger and I spread ourselves around. I would play a game as usual but then pace up and down the room dictating the review while Roger tapped away on his new Apricot computer. Once we had covered all the software releases for a month Roger and I moved upstairs, where Roger helped David with the layout and I produced the halftone pictures. We then decided to make final films of the layout sheets (trying to cut costs and push out even more time before printing).

Another school age reviewer joined the team. At just 13 years old, Robin Candy showed potential, reviewing with the same ruthless criticism I did. On several occasions we made news headlines. Camera teams set up studios in the office and on one occasion both Robin and I had to travel down to Plymouth for a 15 minute slot on a Saturday teen programme showing off our game reviewing skills.

Christmas was always crunch time for us. We had to produce a magazine twice the size in half the time due to the schedule available. Roger and myself worked tirelessly reviewing before moving onto our other tasks. I remember one time working through the night — my feet were killing me so I nipped home and brought my slippers in! We had just three hours sleep before it all had to be repeated. We were all so tired, but the end result was worth it.

Roger and I started to develop basic colour planning (putting colour elements on a page) within the magazine, which became more and more complicated as time went on. It also became more time consuming. It was at this stage that something just had to give, and that something was me. After 18 months of reviewing just about every title ever released for the Spectrum, I told Roger that I just couldn’t do it any more. Totally wiped out from gaming overload, I had to look to another direction for fulfilment. The art department beckoned and so I moved over to further develop the repro side of things, expanding it as the business grew into other areas.

A Commodore title, based on the tried and tested Crash format, was launched in 1985. Zzap 64 was an instant success and became the most successful Commodore 64 title available. Amtix, a magazine for the Amstrad CPC range, followed it. Unfortunately, the hardware never found a large following in the gaming arena despite being technically more advanced than the Spectrum. Failure is a matter of opinion, but while the machine found some business use, few original non-Spectrum ports appeared for it. The magazine lasted around 18 months before being sold to another publisher.

Other magazines came and went. LM (Leisure Magazine) was aimed at the teen market and while it was a nice title, it proved expensive to produce. It also failed to attract the level of advertising needed to survive and as a result was axed after issue four. I was fed up about this at the time. The film planning team and I had just finished the work for issue five and it all had to be dumped. What a waste. It was an immense shame — if the funding had been there then I feel that the magazine would have done well long-term.

A budget horror magazine called Fear was launched shortly afterwards. It was mainly mono and aimed at a niche market — too niche for my liking. It was a bit of a chore to produce but it at least showed a small profit so I guess it was worthwhile.

By this time the company had grown and grown. It was now spread over three sites (we had runners who moved mail from one site to another) and we had 60 members of staff. To give you a sense of scale, we were the local Post Office’s biggest customers. Bags of fan mail arrived everyday, even more when we ran exclusive competitions.

Finally, the decision to move everyone into a single building was taken in 1990. Somehow though, I felt this move destroyed the atmosphere that had inspired everyone. Looking back I guess the company was growing up and I didn't like it! Several new titles were launched but none repeated the success of Crash and Zzap. The market place became more unstable, with more and more magazines competing for an ever shrinking slice of action.

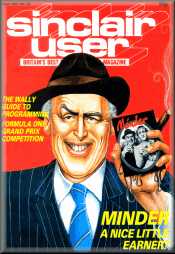

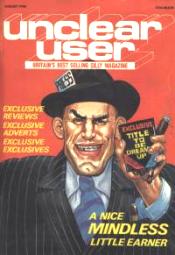

The Crash parody and the Sinclair User cover that inspired it. A bit of fun, but Emap weren’t laughing

The competition (magazines such as Sinclair User) caught on to the idea of our reviewing style and tried to copy it, albeit without the success that Crash had enjoyed. This led to some serious rivalry and things got a little out of hand when we decided to run a section in Crash called Unclear User. It was a total rip off of Sinclair User's design style but the text was re-written to reflect the section heading. Sinclair User issued legal proceedings against Newsfield and forced tens of thousands of copies to be recalled, with the offending pages removed by hand at the printers and then redistributed. An enormous amount of sales were lost and it was a real low point in the history of Crash. We had to print a full apology in the following issue, but the tension always remained between the two magazines.

In 1991 the Newsfield Group (the collective holding company of all the titles) went into liquidation. At that time, the country was in recession and the games’ magazine market place was collapsing. It came as a bit of a reality check for me. It was totally unexpected and came right out of the blue. I was totally devastated. I had so many happy memories, and they were destroyed in an instant. It took a long time to get over it.

Newsfield and its magazines, especially Crash and Zzap, were the bible for the games player and the games industry. They forced other publishers to look at what the consumer really wanted and proved that well written magazines were the only way forward. It’s quite amazing that many of the large companies in the games industry now have at least one ex-Newsfield employee working for them (Future Publishing was started by Chris Anderson who was a Zzap editor for several issues). That must be a lasting tribute to how Crash and Zzap moulded individuals’ minds and inspired people not to follow the pack, but lead from the front.

Europress took over a number of Newsfield titles and about half its staff. The titles sadly only lasted for a couple of years.

It’s quite odd to think that the original three Newsfield creators — Roger, Oli and Franco — are still plugging away in the publishing industry, producing wonderful historical atlases, pet references books, and have contract work with certain blue chip companies. Their company is internationally established in its area of expertise and it just so happens that I still work for them and have done on and off since the demise of Newsfield. Some friendships are difficult to break I guess.

I still dust off my Spectrum from time to time, load up my favourites and relive an age where gameplay was key and graphics left a little to the imagination. My children are fascinated by it all, but still prefer to play on their Xbox. I suppose I can’t blame them. The Spectrum looks so incredibly primitive in comparison.

Newsfield begins life as a mail order company, sending out a free software catalogue to its customer.

After the success of its software catalogue a Spectrum reviews magazine is planned.

First issue of Crash hits the newsstands, priced 75p. Circulation eventually achieved over 100,000 copies a month.

First issue of Zzap 64 hits the newsstands, priced 95p. Circulation eventually achieves over 68,000 copies a month.

First issue of Amtix hits the newstand, priced £1.

LM, Newsfield’s teen entertainment magazines hits the newsstand. It folds after issue four.

Amtix is sold to Database Publications.

The Games Machine, Newsfield’s first multi-format gaming title hits the shelves.

Fear magazine, produced under contract with John Gilbert, hits the newsstand priced £2.50.

Movie: The Video Magazine, designed to cash in on the falling price of films on video, hits the newsstand priced £1.90. It appears popular but isn’t as successful as hoped, closing after issue seven.

Prepress With the Macintosh magazine, designed to cash in on the growth of the Apple Macintosh in the world of professional publishing, hits the newsstand. It eventually breaks even and begins to make a small profit.

The first issue of The Complete Computer Entertainment Guide (CCEG), a quarterly games buyer’s guide, hits the newsstand priced £1.95.

GamesMaster International, a low-budget, fantasy role-playing magazine hits the shelves priced £1.75.

Raze, the renamed, revamped, replacement for The Games Machine hits the newsstand priced £1.95.

The second issue of The Complete Computer Entertainment Guide reaches the newsstand.

The third and final issue of The Complete Computer Entertainment Guide reaches the newsstand.

Frighteners, a Fear spin-off, hits the newsstand priced £1.50. The first issue is pulled off sale after an irate purchaser complains about one of the short stories inside.

With a month to go before its two forthcoming magazines, Sega Force and N-Force (designed to replace Raze after issue 13) are due to be published, Newsfield is put into voluntary liquidation. Europress Publications eventually buys up the company’s assets, turning what was Newsfield into Europress Impact.

After just five issues, Europress Impact sells Crash to Emap. The magazine is incorporated into issue 123 of Sinclair User.

Zzap is renamed Commodore Force to fall in line with Europress Impact’s other games magazines like Sega Force and Amiga Force.

Sinclair User closes after 11 years, taking Crash with it.

Europress Impact goes into receivership. Commodore Force issue 16 (Zzap 64 issue 106) is the last.

Eight years on from the closure of Zzap 64, fans of the magazine create issue 107. It’s available as a free download (in PDF format) from www.zzap64.co.uk. [Since this article was originally written, issue 108 has also been produced.]