SOFTWARE CARES

MONTY MOLE is running for a good

cause this summer as the software business loads up for charity.

Most attention has gone to Backpack, a ten-game £9.99

compilation scheduled for release around 1 September. (The compilation’s

official name is Kidsplay.) The Backpack organisers, led by

Activision’s Rod Cousens and Gremlin boss Ian Stewart, hope to raise some

£270,000 for the National Society For The Prevention of Cruelty To Children

(the Back bit in the title stands for Battle against cruelty to kids). That’s

enough to setup a new Child Protection Team — a 24-hour service which

responds to urgent problems like child abuse.

They’ve got a strong line-up to challenge the Soft Aid compilation,

which held Number One in the charts for three months in 1985 and pulled in

£350,000 for Bob Geldof’s Ethiopian famine-relief. And the Backpack

team, calling themselves Kids Aid, can also take encouragement from the success

of last year’s antidrug compilation Off The Hook which has raised some

£70,000 so far.

Cousens hopes to sell more than 20,000 Backpacks on the Spectrum

alone — and every copy adds to the charity’s coffers. (Distributors and

retailers will be allowed to make a small profit on the game. Otherwise,

Cousens fears, they couldn’t afford to handle it.)

On the Spectrum, Backpack comprises: Bounty Bob Strikes Back (US

Gold), Deactivators (Ariolasoft), Lunar Jetman (Ultimate),

Mailstrom (Ocean), Marsport (Gargoyle), Monty On The

Run (Gremlin), Night Gunner (Digital Integration), Starion

(Melbourne House), Starstrike (Realtime) and Xeno (A’n’F

Software).

Other charities have discovered the high profile — and high returns — of the

micro world. For instance, War On Want is asking software houses for unwanted

stocks of games, which it’ll sell at the ZX Microfairs and other shows to

support its Third World antipoverty work. War On Want discovered the

industry last year when it raised some £10,000 with the WOW

Games compilation.

The London-based fanzine Compute donates its profits to groups

like Children In Need and Ferry Aid (see future FANZINE FILEs). In Cwmbran,

Wales, the computer shop Soft Centre hopes to raise at least £500 in August

for medical research to help children. And when the St John Ambulance

Brigade celebrated its centenary recently, Ocean obliged with 10,000

pieces of software for underprivileged kids.

The software houses will go a long way to emptying people’s pockets — but

this summer they’re giving a bit back.

Reach for the charts: Monty on the Run is part of the

Backpack/Kidsplay charity compilation

LOOK SHARP and B#

RETURNING to the pages of CRASH because he ‘needs the

money’, fave Ludlow heart-throb Robin Candy has gone and got himself into

a local band by the totally awesome name of Adlib to Fade.

After working under the yoke of Roger ‘Trevor Horn’ Kean for several

months, Rob bought himself a spanking new Yamaha DX21 and is now spouting

the joys of Low Frequency Modulators.

Adlib to Fade consists of six members and has been together for

some six months. Fresh from their first gig at little Leominster, at which the

crowd went wild with delight, the Adlibbers have decided to take the summer off

and work on new material, preparing to launch themselves on an unsuspecting

world sometime around September.

As Robin pointed out over a carrot salad by the poolside of his adobe-style

West LA home, any record producers reading this should sign up Adlib to

Fade immediately because ‘we’re Ludlow’s premier band and leave the

likes of U2 and Curiosity gasping in admiration.’

Pictured here are the infamous Adlib to Fade lads themselves posing

around Ludlow Castle. From left to right are Jonathon Harris (bass), Jason

Howard (keyboard and earrings), Andrew Thomas (drums and wrecked cars),

Lee Watkins (guitar, vocals and perms) and last but by no means least

Robin Candy (keyboard, vocals and money).

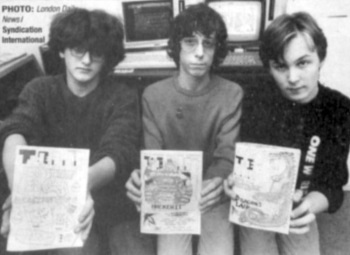

THE BUG THAT ROARED

The dark side of FANZINE FILE — how one small mag shook the software

giants

THREE YEARS seems like forever in an industry where

1984 is ‘ancient history’. And for a fanzine three years is more than ambitious;

it’s well nigh impossible. But this summer four North London fanzine editors

are trying to hold off the end of a three-year era — the end of the small,

smudgy but outspoken Bug cutting a swath through the software jungle.

What could a team of teenagers write that would alarm the industry so much

that Gargoyle Games struck them off its mailing list for review copies?

Gargoyle slammed The Bug’s ‘extreme political views’ in its letter to

the fanzine in February 1986. And The Bug’s controversial break with

Creative Sparks Distribution (CSD) in May was certainly over its strong

content, whoever you believe.

The stories differ. The Bug’s editors charge that CSD, its

distributors, objected to the fanzine’s review of their Commodore game Cyber

I (on the Super Sparklers label) in The Bug’s April issue. But CSD

Managing Director Henry Kitchen gave CTW (Computer Trade Weekly) another

reason; the fanzine’s language went too far, he felt.

‘I couldn’t justify supporting them,’ Kitchen said after listing some mild

swear words The Bug had allegedly used.

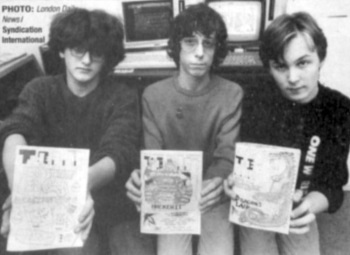

‘Extreme political views’: left to right, Danny Marcus, Jeffrey Davy and Jaron Lewis of The Bug

POLITICAL BROADSIDES

The Bug has never kept its views to itself. Though most

amateur computer mags put their effort into visual presentation, The

Bug’s six-by-eight inch pages have limited it to a drab standardised format

without sophisticated artwork.

So almost uniquely among fanzines it’s based on words, on passionate and

often well-written text which rarely indulges in the puerile fooling of many

fanzines. And as well as reviewing games, The Bug tackles the issues;

the merits of marketing, the legal obligations of software shops.

Sometimes The Bug is coloured by controversial politics, too. Its

reviews of Falklands 82 and Battlefield Germany harshly criticised

the warlike PSS mentality. And what upset Gargoyle was a Bug ad attacking

Rupert Murdoch’s treatment of his News International print workers — an ad

placed by The Bug’s editors themselves.

Even now, as The Bug plans a series on famous people and computers,

they won’t print the Prime Minister’s contribution — because ‘it’s a Party

Political Broadcast by the Tory Party,’ according to coeditor Jaron Lewis.

And in a recent letter to CTW, Lewis and his fellow Bug founder

Jeffrey Davy pontificated on sexism in games (‘Mag Max stars a MALE, Greyfell

stars a MALE cat...’)

So it was no wonder that when the break with CSD came, Lewis and Davy leaped

into the argument with a press release, a diatribe against the software industry

in CTW — and some damning allegations against CSD.

‘We did have a contract with CSD, which they broke,’ says Lewis. ‘They

didn’t seem to think very much of the contract.’ The Bug had a hard time

getting CSD to give them their usual 250 copies from the 1,500 print run of

that contentious April issue. And the distributors added insult to injury,

Lewis alleges, when CSD executive Leigh Richards hung up on the two editors.

THE GOODNESS OF THEIR HEARTS

CSD, after their first criticisms of The Bug’s growing

pains, were anxious to play the issue down. ‘The whole thing has been initiated

by them,’ says Managing Director Henry Kitchen. ‘The Bug are trying to

make mileage out of it.’

The acceptable face of software? CSD’s Henry Kitchen

Certainly CSD sought neither fame nor fortune from their brief Bug

sponsorship, which started last Christmas. The company based in Farnborough,

Hampshire had only an unobtrusive credit at the end of The Bug — yet

they met printing costs of some £1,200 an issue. And most copies of the

40p Bug were distributed by CSD through its software retailers, too; the

fanzine had only a few for subscriptions, schools and friends.

‘Sponsorship is something we do because it’s helpful to people,’ explains

Kitchen. ‘Whenever we’ve given something we give it — and we don’t feel the

need to shout about it.’ So his colleague Richards won’t name CSD’s other

fanzine sponsorships, which he describes as done ‘out of the goodness of our

hearts’.

Pressed on the Bug issue, Kitchen admits ‘the magazine was not what

we expected and that’s why we pulled out’.

‘BY AND FOR CONSUMERS’

And there it is. The Bug has gone back to photocopying;

they’ve found two software-industry sponsors for their Issue 30, but nothing

permanent; and as ‘a magazine by and for consumers’ they’ll carry on arguing

with the industry’s faults.

‘I expect we’ll survive,’ says Jaron Lewis. ‘We’ve survived coming up to

three years.’ Davy even sees a silver lining in the CSD cloud; ‘Looking forward

now, it’s going to be easier to survive, because we’re more wary. We’re looking

more closely at things after CSD.’

While they’re unsure about the date of their next issue — exams, as much as

enemies, are holding the 15- and 16-year-olds up — The Bug’s editors

plan to fund the fanzine without sponsorship, if necessary.

‘Because advertising is immoral,’ explains Davy light-heartedly, ‘we’re

going for the Bug Adopt-A-Page scheme. They put forward a nominal sum

(£20 a page) and put what they like on the page... so long as it’s

not sexist or racist or heterosexist.’ Among the adopted pages in the next

Bug is one bought by... CSD.

But here comes the crunch: does The Bug matter to the industry? One

top marketing person observes, ‘When the question comes down to it, ‘would you

advertise in that publication?’, I’d say ‘no’.’

And do The Bug’s reviews, positive or negative, make any difference

to software sales? Or have their letters to the trade press and their

pretensions to megamagazinedom (the Bug Publications UK ‘newsroom’ claims a

News Editor and eight telephone lines on Jaron Lewis’s one number...) given

the issue a false importance?

KICKING THE TEETH THAT BITE THEM?

Most software houses feel that despite a recent boom in

fanzines — one large company receives three or four a day — sending them review

copies does more for goodwill than for good sales.

And Nexus’s Ian Ellery voices a still-common suspicion: ‘A lot of fanzines

just set themselves up so they can get free software. It’s worth their while —

but not worth anybody else’s while.’

The PR people agree, though, that The Bug’s the best and that

review copies aren’t wasted there. Jeffrey Davy, of course, backs them up — and

believes a single fanzine could make a difference.

‘The growing number of fanzines doesn’t help anybody,’ he says. ‘We look in

the CRASH FORUM, and every issue there’s a letter saying ‘me and a few friends

are going to start a fanzine’. Hundreds of them... it’s ridiculous. It’s much

better to get in touch with a working fanzine and work for them.

‘The main problem is people who get software and haven’t got the compulsion

to carry on. Things like Your Sinclair’s Fanzine Of The Month are

really bad, because it suggests you should start your own fanzine and send it

in.

‘People spend months making the fanzine really pretty and win the prize,

and that’s a kick in the face for the people who do it every month.’

BARNABY PAGE