THE MESSIANIC APPROACH TO COMPUTER SOFTWARE

Or the Software Gospel according to Croucher...

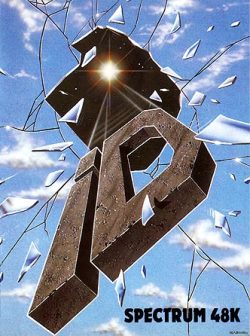

Last month we took a look at a game which appears on CRL’s New Wave label. It grew from an initial concept devised by Clement Chambers and was programmed under Mr Croucher’s conceptual eye by Colin Jones. This month we take a look at the man who acted as midwife to ID and who is assisting in the development of Darkness at Dawn, an adventure which employs sound and light rather than text input.

Since leaving Automata Mel Croucher has been planning for the future. He feels the software industry is going to have to change its approach radically over the next few years as technology advances. Sitting next to him in a London pub, hemmed in between a fruit machine on one side and a jukebox on the other, GRAEME KIDD learnt a little about Mr Croucher’s view of software, the advent of devices that will allow videodiscs to be interfaced to home computers and the potential they have for revolutionising entertainment...

Mel Croucher has been involved in the home computer software business pretty much since it started — with Christian Penfold he founded Automata which gave birth to the PiMan. They refused to be involved with games that featured mindless murder of pixels, and consistently released games which were different to those produced by the mega-combines which dominate the industry today. His most ambitious project to date is DEUS EX MACHINA — an entertainment involving a soundtrack synchronised to the screen action. DEUS is much more than a game — and has been dubbed as a piece of software ahead of its time. Now ID has been released.

Clement Chambers, the boss-man at CRL, is the person who first dreamt up the idea which finally surfaced as a computer program called ID. He had been toying with the possibilities of launching some totally different software and jotted his thoughts about a particular concept involving artificial intelligence on the back of a grubby envelope.

This envelope found its way to Mel Croucher who agreed to develop the concept a little further with programmer Colin Jones. Once you load ID you find a personality inside your computer who has a mysterious past and a total tack of trust in you and the outside world. It is your task to converse with ID, taking into account its changing moods and moments of fear and jubilation as you try to draw out its secrets.

ID-EOLOGICAL STANCE

ID is very different to the normal run of games software and is the first new release that has involved Mr Croucher for more than twelve months. “It has never been particularly attractive for me to play safe”, Mel explains, “and when Clem contacted me with an embryonic idea I was attracted to it because it is using computers for what in my opinion they should be used for — to stimulate. It doesn’t matter whether the micro stimulates tears, laughter or whatever, a reaction is important. If New Wave can achieve that, more power to it, because nobody else is doing much in that direction.”

ID is perhaps Mel Croucher’s second public step on a path towards using computers in a very different way. Since leaving Automata (on April Fool’s Day last year — a joker to the end) Mel has spent months travelling round Europe. meeting hardware manufactures and learning what’s likely to be available in the next couple of years. He’s impressed by what he has seen, and the possibilities that will open up in the near future for new kinds of software: “Five, six years ago the concepts were much bigger than the machines, much bigger. I wanted to do Deus Ex Machina on the 1K ZX81 ... now the concepts are piffling compared with the hardware we’ve got available. There’s no memory restriction any more, there are ways you can get around that no problem at all. Graphical definition is getting pretty good, as is the capability to reproduce sound. Now the concepts are trailing behind the hardware — the hardware isn’t even on the shelves yet, but it’s there; it’s ready now but no-one’s launching yet. We’re just on the threshold of a beautiful new toyshop.”

NEW CONCEPTS

Mr Croucher is cagey when it comes to revealing details of the projects he’s currently working on — but they are firmly placed in the future. “I’ve been working very hard since I left Automata, and if anything comes to fruition I’ll be happy to talk about it when I’m convinced that it’s going to work.” He explains his reticence: “One of the faults of this business — indeed of any business really — is hype. I just don’t want to be guilty of saying I’m working on something really great and then it doesn’t happen.” It’s clear, however, that Mel Croucher’s plans involve much more than conventional games.

“The days of passive entertainment are over,” he explains, “for the past five hundred years human entertainment has been passive. Unless you are actually playing on the stage or playing in the football team, all received entertainment is passive. If you read a book then you can’t affect the plot — you can start at the back page and work forwards, but then you are an idiot! If you watch a film, it’s even worse because you are given the images and you can’t even think up the images for yourself. And so on.

“With the advent of the computer things changed for the first time since Gutenberg printed that first bible — the reason I go back five hundred years to Gutenberg is because that was mass entertainment. Before that bible was printed entertainment was spoken and you had folk tales and songs and the audience could participate. They could either change the story when they told it on, or join in the choruses and so on; it was active to a certain extent.

“Home micros allow entertainment to become active again. You can participate and whatever you do affects the final outcome, hopefully.”

REAP AS YOU SOW

In some respects, Deus Ex Machina is recursive in that it goes back on itself — you have to go through it several times before you can actually start to play it. There are a lot of levels in Deus and it’s easy to take the program as a set piece which doesn’t actually change. “You get out it what you put in,” Mel continues, “that was the primary motivation for Deus and has got a lot to do with ID — what you get out of it is what you put in — that’s what’s going to happen next in entertainment.”

Mel explains what ID is intended to be — “I hope there are a number of levels. At its simplest level the program should be the verbal equivalent of Geoff Minter’s Psychadelia — it will just burble along, generating phrases which should entertain people at parties for instance. That’s if you give it nothing at all, if you don’t contribute. At its most optimistic level, if you ever get through the game and achieve total trust, then ID will have learned from you — and don’t lie to it, if you lie to it then you are only lying to yourself — then it will, I hope, reflect aspects of your own personality that you weren’t aware of before. In the best possible case you’ll want to play it all over again, to do it better next time.”

“There’s a lot of humour in ID which you can actually get into. I’ve got a lot of experience of being in the wrong pace at the right time and vice versa to draw upon, and lot of it has come through. It’s the humour of despair almost. Can your readers read French? ‘Si je ne rire pas je pleurerai’ — never a better line written in French. If I didn’t laugh I’d cry and so be it. Let’s all laugh. I don’t see anything funny at all about shooting things down, killing people and all that. I find things extremely funny in terms of wordplay or soundplay or concept play, that can be hilarious. With ID you can make such a total tit of yourself by lying to it or contradicting yourself later on, it’ll remember and if you start changing your mind it’ll start losing trust. Some of the wordplays are not as daft as they would appear to be. If ID starts saying ‘Mummy is the root of all evil’ it’s not an accident — he means it, because you’ve told him something about your mother perhaps. So it’s got those link in it.”

“There’s a game in there, in discovering ‘Who is ID?’ Nine little games, for the nine individual previous incarnations and one big one. If you want to play a game, you’ve got a game there but there’s also something else...”

BYE BYE PIMAN

The association with CRL which led to ID’s release goes back to an early Microfair where Mr Croucher bought a very youthful Mr Clement Chambers his first pint of beer! In those days, the pink suited PiMan, star of PiMania, made regular appearances at ZX Microfairs, often accompanied by Mel wearing weird and wonderful costumes, and was the star of a comic strip which adorned the back page of Popular Computing Weekly. But the PiMan is no more: just before we met Mr Croucher, he had just written the PiMan’s obituary in his weekly gossip column in a trade paper. Why?

“Because whatever happened to the PiMan in the future, whether he re-emerges under a different guise or with a different owner, my personal involvement has ceased. Even after leaving Automata last April and the Popular Computing Weekly strip had ended, Christian Penfold, Robin, who draws the cartoons, and I would regularly get together over a gallon of beer and poke three fingers up at the industry between us in the weekly comic strip in Computer Trade Weekly — some of which were spectacular.

“It’s interesting that Clem in his office upstairs has the final strip from Popular Computing Weekly — ‘Whatever happened to the Piman, Daddy?’ — on the wall. And I’ve been to a number of offices over the past year where that has been on the wall. It meant quite a lot to me. The comic strip delivered some really spectacular prods at the industry. The PiMan was a cynical child who never grew up... or a cynical old man who never grew up, they’re the same thing. The way that the industry has evolved it can only be static. He had his day, I’m very grateful to him — thank you very much — I did okay by him and he did okay by me. So yes, I mourn his passing and look forward to tomorrow.”

SENSELESS VIOLENCE

Speaking both personally and through the PiMan, Mel Croucher has always held strong views about shoot ’em ups: “I find violent games very unpleasant for a number of reasons. Firstly they are pathetically inadequate, because the characters depicted are still awfully basic — just pixels — and the sounds generated are squeaks and beeps and the end product has nothing to do with Friday 13th or Rambo, absolutely nothing. They are dressing up hackneyed ideas. That’s my first objection. Secondly, they are totally derivative. I think the computers that we have now offer tremendous freedom of expression for any concept. Thirdly I think they are socially destructive. I’ve been saying it for years and people are very bored with me saying it like that but I think it is very dangerous to encourage young people to believe that winning is to do with killing. I think that’s extremely dangerous. We have a new generation coming who will have no qualms whatsoever about pulling the trigger in any circumstance.”

Strongly held opinions indeed, but more importantly Mel feels that the software industry has gone stale. There are only two basic types of game in the world from which all other games derive, he believes: games that have their roots in chess, involving strategy and so on, which require the player to apply intellect, and reaction games in which you respond to what you see. Most of the established games and puzzles, like Draughts, Chess, Towers of Hanoi and so on were converted to home micros a long time ago. The software industry is growing stale, he feels.

“The hardware gets better. The software gets better. There’s a lot of good software around at the moment; it’s never been so good in fact but things move on. It’s derivative, it’s all derivative. The programming is superb now but the concepts are all stale. It’s all very well to sign mega deals and licence various things — either buying licences or selling licences — but at the end of the day we are down to the programmer, who in turn relies on the concept. It’s great to say ‘I’ve come up with the greatest thing since sliced bread’, but sliced bread goes off after a day. I stole that line from someone, by the way,” Mel adds, smiling.

Software houses tend to follow each other’s lead — once one Karate game has come onto the market, several versions follow. For each ‘new’ type of game, several clones follow. Arcade conversions are becoming increasingly important in the list of new releases. It’s all derivative and lacking in originality according to Mr Croucher...

“Last year I was in the company of a very large and well-known software house wherein the man was dressed in a grey three piece suit and looking worried, and his PR boys and girls were all very well turned out, plying people with this, that, and the other, and the structure was a wonderful pack of cards. Who wrote the programs? In they came, like the seven dwarves. These little children came in and were given a shandy or something. The whole company stood or fell on what these little kids could turn out. When I say kids, I mean kids — we were talking to fourteen or fifteen year old programmers. They can only be derivative — it is impossible for them to come up with an original idea, absolutely impossible — for even if they do, they haven’t got the vocabulary to express it.”

PASSING OVER THE BUCK

Mr Croucher’s approach to writing software for computers doesn’t involve making a fast buck. His prime motivation is not money — he gets involved because he wants to, because he loves it. “I just want to entertain people,” he asserts, “the mechanism of the computer is just like a blank sheet of paper or an empty reel of recording tape or a set of tap dancing shoes. There are no deep philosophical messages, I just want to entertain. In the sense of the cinema, you can entertain and make people cry or laugh, or instil some emotion: I want to do that with computers. In the past I’ve been involved with radio, music, the written word and so on. For the first time it all comes together. It’s totally different this time round.”

“I don’t like what is happening — I’m very unhappy about computers and their effects on us. I’d much rather people spoke, sung or made music — it’s a lot more valid for the people concerned. Whatever I’m doing in the future I would hope I can beat the pornographers to using the new technology — because they’re going to come in, no matter what happens, because their prime motivation is the fast buck. They’re going to make a fortune out of the new technology — with customised pornography or whatever.”

Despite being voted program of the year in the Computer Trade Association’s annual awards and despite collecting almost universal acclaim, Deus Ex Machina was not a roaraway commercial success when it first appeared on the Spectrum. It is currently enjoying a chart position on the Commodore, now that it has been released by Electric Dreams, however. It wasn’t a commercial success the first time around, but it was fundamentally different to anything that had appeared on the Spectrum when it was released and hasn’t been surpassed yet. Mel Croucher intents to continue along the path he set out on with Deus. Musician, writer, game designer, software that involves Mel Croucher is very different — is it art?

“You’d have to define art! I hope so, that’d be great. Yes, what I’m involved in is art, if you define art as something that the artist has to do. Yes, if art is something that nobody ever gets paid for (thanks for the cheque Clem!). The artist can never make a living out of his work, it is the businessman who has to make the living, therefore you have to compromise.”

CHANGES IN MIND

Art or no, things are going to have to change in the software industry as it is viewed by Mel Croucher. “Now all the shakeouts that took place over the last couple of years are over the industry is in the doldrums. It doesn’t really matter who owns what now, it’s the concept that’s becoming important. The kids are getting bored... how many machines are stuck away under the stairs out of all those that were sold — over half?”

“In this country at least, we’ve been in the doldrums for a couple of years — there have been no major new concepts and I think that is about to change. Perhaps this year, certainly within two years. It’s taken four or five years for everyone to get over Ping Pong and such games, and the whole computer bubble is about to happen over again. The major difference is that once a piece of work is out of my hands it goes on to whoever participates at the other end, the end user. And that’s fascinating.”

And more than that he would not reveal.