Talented people of all ages and a variety of backgrounds seem to be drawn towards the business of producing highly imaginative micro computer games that we all enjoy so much. Michael Broomfield went to Bath to meet Malcolm Evans, former micro processor scientist, and his programming team at New Generation Software. There he discovered the ingredients required to produce a game like the company’s latest hit, Trashman.

It is astonishing how an industry as young as the Microcomputer games business is so rich in talent. But almost as surprising is the variety of talented people from all types of backgrounds and age groups. What they do share in common, however, is an all-consuming interest in microcomputers and, for those involved in programming, a desire to write games which are better and better.

This variety in talent is reflected perfectly in New Generation Software, who are lucky enough to have three exceptional programmers of totally different backgrounds with their own unique styles.

Malcolm Evans, whose latest creation is the exciting and hilarious hit game Trashman is the founder of New Generation Software. Paradoxically, perhaps. Malcolm has a background in hardware. He has a B.Sc. in electronics from Portsmouth Polytechnic, and after graduating he was employed by Marconi for 11 years on spacecraft design. But by the mid 1970s Malcolm’s career was gradually heading towards computers. After Marconi he worked for Smith’s Aviation at Basingstoke, co-ordinating research for computer-based engine control. He also wrote test programs for the hardware he designed. Then in 1979 he moved to Bristol as a microprocessor scientist with Sperry Gyroscope. Through this appointment he became familiar with the technology used in the earliest home computers.

Because of this interest in April 1981 Malcolm’s wife bought him a birthday present that was to change his life — a ZX 81, which completely hooked his imagination. By November of that year he had written his first computer game.

On the other hand, another of New Generation’s programmers, Paul Bunn, is only 16. He left school with seven O-levels and decided not to continue his studying because, as he say, ‘A-levels are boring’ and he wanted ‘to write games’.

After being given an Atari for Christmas two and a half years ago Paul has been fascinated by computers. At school he did O-level computer science — the course included both history and the theory of computer. His Atari, which Paul has always considered to be the best microcomputer on the market, was very useful in his studies. In fact it helped him complete a pontoon program and a maths education program for his project.

When he was still only 15 years old Paul replied to an advertisement in a computer magazine asking for help in writing a book on the Atari. In fact he was invited to write it all himself. The book, Making Most of Your Atari, published by Interace, included all his programs written to that date, 14 games in all in basic plus a tutorial about some of the points which had not been raised in the Atari manual. The book was very successful and with the royalties Paul was able to buy a disc drive.

Within just one month Paul wrote another book, Games for the Atari, published by Virgin. This had 21 games in basic but with machine code subroutines. The book was so successful that he was able to buy a modem, a touch tablet, an Atari 800, an SX printer and an interface module. Paul’s latest book, Getting Started on Your Atari, published by Futura, is in the shops now.

Paul joined New Generation Software after he saw an advertisement in the Bristol Evening Post. Says Paul, ‘I leapt out of the chair and dialled the number immediately because it offered everything I wanted.’

The decision by Malcolm Evans to form New Generation Software was not so spontaneous. Rather than leaping out of his chair Malcolm engaged in a slow thoughtful process which led him inevitably to the setting up of New Generation Software in the city of Bath.

Malcolm designed his first game in 3D, really just to see what his ZX 81 could do. Someone suggested that it was good enough to sell, and so by February 1982 3D Monster Maze was launched. Soon after this Sperry Gyroscope closed down in Bristol and rather than move to Bracknell Malcolm took voluntary redundancy and concentrated on computer games. From the outset New Generation and Malcolm Evans have become synonymous with 3D graphics, of which his second game, Escape, is a famed example.

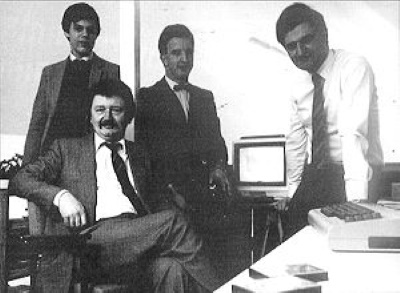

New Generation staff (left to right): Paul Bunn, Rod Evans (seated), James Day and Malcolm Evans.

From now on things just kept on improving for Malcolm and New Generation Software. In June he obtained his first Spectrum, by November he had written Escape for the machine. This was followed by 3D Tunnel in February and Knot in 3D in April 1983. At about this time Malcolm was joined by his brother Rod. Rod is now the managing director of New Generation Software, thus allowing his brother to concentrate on what he is best at and enjoys — writing games. In September 1983 Corridors of Genon was released and in February of this year what is widely expected to be their best hit to date, the highly imaginative Trashman game was launched.

New Generation’s other programmer is James Day. At 19 years old this is James’s first job, and next year he is planning to go to college to read physics and electronics. Already he has developed several games.

Malcolm, James and Paul work very closely as a team meticulously considering every detail, ensuring highly finished quality graphics. Malcolm believes de-bugging is very important and ensures every sub-routine is thoroughly checked. That’s why their games are so polished. After all, the amusement in Trashman partly comes from the realism of the graphics. For example, when the Trashman develops a limp after being bitten by a dog, or when he slows down with the weight of a dustbin.

The amusing messages that come on the screen in this game show how much thought has gone into it. That’s why Malcolm believes that hardware must improve before he can develop more complex games.

The quality and finish of New Generation’s Games has so impressed one of their rivals, Quicksilva, that they have made an agreement to market all New Generation Games world-wide, for the Commodore 64.

With recognition like that New Generation’s programmers must have a shrewd idea of what makes a successful game. Malcolm says it must have ‘addictiveness and good presentation’. Paul also thinks ‘addictiveness is essential plus good graphics and sound’. He also thinks a game should be ‘something different, like Trashman’.

So that’s the team: Paul, an ambitious teenager, typical of his generation, except for his astonishing aptitude for computers. Malcolm, an electronics wizard who was lucky enough to discover he can make a business around his love of microcomputer programming, and James, soon to go to university but in the meantime an essential part of the team.

All very different, but all determined to write excellent programs.