Enter the professional programmer: Steve Turner and his assistant, Andrew Braybrook have recently entered the field of writing software for home computers on a full time basis. Their first program, 3D Space Wars has reached new heights of realism in its graphic design and ingenious construction. Andrew Hewson writes after his recent meeting with Steve and Andrew.

Steve lives in Essex with his wife and little son, Mark (with another child expected soon). He was thirty this year, a fact that made Steve think carefully about his future and decide to take a radical and some would say risky step.

Steve began to learn programming when he was about 15 years old. His career in computers really started when he attended one of the early TOPS (Training Opportunities Scheme) courses six years ago. After this he entered the Civil Service as a Clerical Assistant. He quickly became a programmer despite not having the necessary two years experience. He became dissatisfied with his work however and left the Civil Service to join one of the world’s largest insurance brokers.

He worked for four or five years making financial developments on ICL and IBM mainframe computers. At first he enjoyed the atmosphere in a big insurance company who insure, through Lloyds, everything up to Concorde and the Space Shuttle. He became a specialist, converting systems from other machines to IBM etc. He was appointed a team leader working on his own systems.

Steve has always been interested in home computers, and owned a ZX80 for some years. He became more interested in the hardware — how the chips and circuits work and so learned about assemblers to help him understand more about it. He also tried writing games on the ZX80 but soon decided that that was a dead loss.

When the ZX81 was introduced into the market, Steve decided not to buy. However, when the Spectrum came out, he must have been one of the first people to buy the new model and despite working full time still, he laboured in earnest to get the most out of this new machine. He dreamed up some good ideas for games and soon found that to achieve the effects he wanted, he needed new techniques. The games on the market at that time were, in his opinion, rather amateurish in many cases. For months, he worked into the small hours of the night perfecting new techniques and eventually produced a game, unlike any that had been written at that time. He submitted it to four software houses and three wanted to market it for him.

At this point, Steve was beginning to feel disillusioned with working for someone else. He decided that after spending over half his life enjoying working on his home computers in his own time, he was ready to become self employed and use his talents for his own benefit. When Hewson Consultants offered him a contract he decided to start working full time on writing software for home computers.

The game he wrote, 3D Space Wars took about five months to develop. Most of the time was spent in detailed graphic design and of course in developing the new techniques needed for this powerful game. Since then, Steve has developed 3D Seiddab Attack. This took three months to produce, most of which was spent designing it. Using many of the techniques learned with 3D Space Wars the actual writing took less time than its predecessor.

Now Steve is concentrating on another new game, called Lunar Attack. So far it has taken three months development and involves a lot more than either of the two previous games, because Steve is using the full potential of the 48K Spectrum for the first time. Previously, the graphics had been compromised so that the games would run on a 16K Spectrum.

Steve has other ideas which at this stage he is not prepared to divulge. The market for home computer software, Steve feels, is going to change, and he would like to see the whole standard of software improve. He would like to see more arcade quality programs, professionally produced and less amateur-basic programming which makes up so many at present. The public has often in the past been disappointed by the programs which have not matched in performance the pretty pictures on the boxes.

In the future, Steve thinks that people will expect more and more from programs. He expects more powerful programs with more depth — more like novels than sketches. He sees the welding of the graphical and word type adventure game, so that players can continue for hours with the same program. At present adventure games rarely have any graphics — perhaps just stills. Steve sees no reason why far better graphics cannot be incorporated. In the long term future, Steve predicts a major revolution in the entertainment industry. This would involve interactive entertainment: instead of watching a film, you’ll be able to take part in the film and help set the course of it. The film and TV industries will have to work with the computer industry. Already in the US they are starting to use laser disc technology for the storage of pictures. This forms a background to the storyline which is handled by a computer.

As a force on the market, Steve soon realised that his impact would be greater if he could employ others of his own calibre. He also would find it beneficial to be able to bounce ideas off someone with the same technical expertise. So he invited 23 year old Andrew Braybrook to work with him.

Andrew worked at Marconi in Chelmsford, where he was a trainee programmer in the computer centre. Using CMS, CICS and Cobol, but few assemblers, he worked with a suite of IBMs. After four years he had become a trainee analyst and programmer. He had always written computer games in his spare time, using Cobol to throw up games rather than text on the firm’s computers.

After two years at this job, his Dad bought Andrew a ZX81, and he began to dabble in Basic. Andrew bought himself a Dragon 32 which he found preferable with its better keyboard and colours to play with. He saw Steve Turner’s work and became interested in it. He began to try to collate his ideas on the Dragon to see what could be achieved.

Three months ago Steve offered Andrew the chance to join up with him in his business and Andrew took it up without a second thought. Now his computing skills are more obvious and appreciated than when he worked in a big company, which gives Andrew a lot of satisfaction.

Steve and Andrew find that in the first stages of designing a game, they work mostly individually, with a strong competitive spirit to produce the best idea. In the final stages of game design they work together with plenty of discussion as they fine-tune their games. Steve works for the most part on the Spectrum, whilst Andrew works on the Dragon. They are each experts on their own preferred machines, yet don’t really know each others machine. On the whole, Steve does most of the graphical design work and Andrew works more on the programming techniques. Andrew feels that the market for Dragon software is very undeveloped with plenty of room for his exciting programs.

Design is problematic. It is not easy to dream up a good idea. Steve doesn’t think it is the sort of thing you can teach anyone. He doesn’t think there are any rules. He wonders if in the long run it needs a different sort of person to come up with the ideas. He gets some of his ideas from the pub on a Sunday!

Steve is quite happy to leave the distribution and marketing to the experts at Hewson’s, so that he can concentrate on the artistic part of producing the games. He feels that the talent needed to come up with these brilliant games is perhaps not the same as that needed by a skilled artist, but that perhaps the home computer game is a difficult medium to use with just as many challenges as paint and canvas. Ultimately we like to see something nice on the screen. He wonders if one day his work will be displayed as 20th century art in art galleries? I wonder what games will emerge when Steve enters his abstract period??

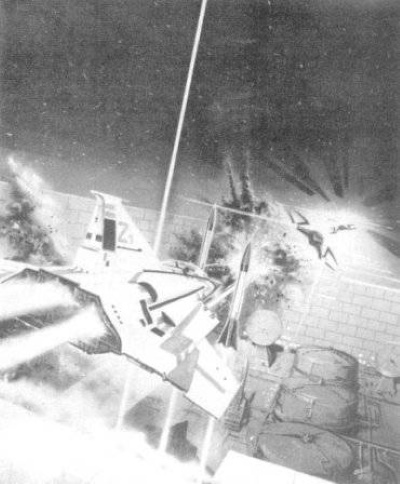

At the 9th. ZX Microfair in December, Starzone’s game

Zaxxan caused quite a stir when it appeared on the Crash Micro Games

Action stand. The game on which it is based is, of course, the famous arcade 3D

scramble game Zaxxon. Since it showed up in British arcades (and rarely at

that) Zaxxon has become a bit of a cult. Naturally Spectrum owners were eagerly

awaiting the inevitable appearance of a version for their machine. Months went

by — nothing. Was everyone frightened of doing what would be a very difficult

program on the Spectrum? It seemed so. But then a brand new name,

Starzone, appeared with a small black and white ad for their

Starzone is not a big, financially well heeled company at all, in fact they are four young men with an average age of only 17.5, and Starzone, which has operated at a profit and continues to do so, was started with hardly any money at all. David Cowell (the oldest at 19) disarmingly told us that the basic idea had been to raise insurance money for cars, which could be done cheaper through a company! David refers to himself as Starzone’s Co-ordinator. Tim Lake (18) is the Advertising and Promotions manager, which leaves brothers Tim Mardon and Nial Mardon.

Tim, also 18, describes his function as a sort of accountant, whilst the youngest of the group, Nial (15) is the senior programmer. It was Nial who wrote Zaxxan.

The three older members are between school and university and intend continuing with their education despite the company, while Nial is still at Abingdon school. As they talked, it became apparent that the common link is Abingdon School (near Oxford), where the other three were also in attendance. One of their other games, Dalek Dan, has been written by another pupil at Abingdon, Malcolm Salmon. David added, rather apologetically, that the third game, River Raider, just happens to be by another Abingdonite. We began to suspect that Abingdon is trying to rival Liverpool as Silicon Chip Hill!

All four members of Starzone have computer programming experience but Nial is the most experienced in Z80 machine code. He used to own a TRS 80 and had developed a ‘Scramble’ type game for it, but when the Spectrum came out he bought one and the first program done for it was Zaxxan. As the TRS 80 and Spectrum both work on the Z80 processor, there was little problem for Nial in adapting to the needs of the Spectrum.

Zaxxan was in fact ready quite some time back, but the boys’ ‘A’ levels held up operations, so that the game was only ready to market in September. Test ads proved there was a market for it, and now they have commissioned full colour artwork for the inlay cards.

Meanwhile Nial is working flat out on a new game with the working title of Supercharger. It’s a ‘Pole Position’ type game. At the ZX Microfair they had a good chance to look at all the various competitors in the field and decided that no one has yet come up with the definitive Spectrum version. Nial is ‘sub- contracting’ the title screen and sound effects, which are intended to be spectacular, and he is aiming for a highly playable game incorporating features like humpback bridges, tunnels with only headlamps seen, a suspension bridge, hills, bends, an ambulance to watch out for, and the best 3D perspective view yet seen. There will be a hi and lo gear change with ice on the road as an extra hazard to the other cars. He’s also looking into the possibility of rain (giveaway mackintoshes with every cassette perhaps?)

Meanwhile the Starzone team — a very calm bunch too — sit (metaphorically) and wait for the reaction to Zaxxan. They got a mixed reception at the ZX Microfair with people either loving it or complaining it wasn’t enough like the original. ‘People are very unrealistic in their expectations of the Spectrum,’ said David Cowell philosophically. But their Zaxxan remains the only version, and it’s a very good one. Let’s hope University doesn’t entirely swamp their programming energies. We mustn’t be complacent, we need new writing talent all the time.