The first thing you notice about CRASH is the cover. Oliver Frey is responsible for all the covers — and a great deal more in the way of illustrative material that graces the pages of the magazine.

We made an appointment with the Olibugs, and were granted an interview with their master, who works on a desk covered with little bottles of Luma ink (used in his airbrush), right at the pinnacle of CRASH Towers in the draughty Artroom Garret. There was a time, before CRASH started, when Oli made his living as a freelance illustrator — but nowadays he’s holding down what must seem like the equivalent of a couple of full time jobs, painting covers for CRASH, ZZAP! and AMTIX, as well as Christmas posters, Olibugs, the Hall of Slime — and lots of fiddly bits, like logos, competition illustrations and giant capital letters to pretty up the text in all three magazines produced by Newsfield.

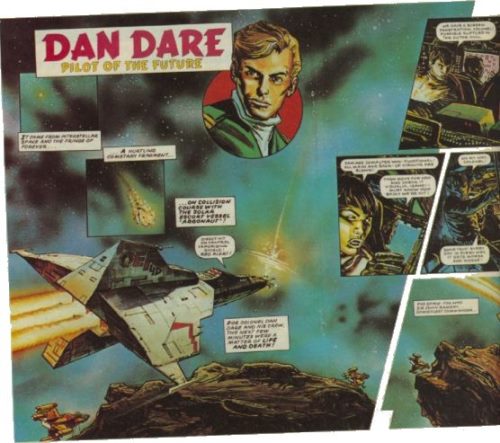

THE TALE BEGINS nearly thirty years ago, when the Frey family came to Britain from Switzerland. The very young Oliver Frey started school and was soon introduced to Eagle by his comic-mad classmates. Oli was immediately taken by the quality of the artwork in Eagle, and immersed himself in the doings of Dan Dare and his battles with the Mekon. Already exhibiting an artistic leaning, Oli began copying drawings — and his first brush with fame came when a teacher caught sight of a giant cowboys and indians picture the nine year old artist had produced and wheeled him round all the classes in the school showing off his work!

After a few years the Frey family moved back to Switzerland, and Oliver’s education continued — a friend in England continued to send copies of Eagle to him, however, and his weekly dose of comic fun came through the post. He was addicted to the work of such greats as Don Lawrence (Trigan Empire), Frank Bellamy (worked on Dan Dare and other features in Eagle) and Frank Hampson (creator of Dan Dare). Indeed, Oli sent several of his own drawings into his favourite comics, and was once rewarded with a reply from Don Lawrence — it wasn’t the last time they were to have dealings. Oliver decided that he wanted to become an artist, and he persuaded his parents to let him to take a correspondence course in illustration while he was at school. They paid for an American course called The Famous Artists, a series of three books written by a team of a dozen illustrators. Each of the thirty six lessons ended with an assignment, which had to be completed and sent off to be marked.

By the time Oli finished his A levels, he had completed the course and was keen to become an illustrator. Or a film producer — he had been making films with an 8mm camera, with his brother Franco and sister Lauretta as stars. Or an army officer (military service is compulsory in Switzerland). Or a diplomat.

The London Film School attracted his attention, and during a visit to England he approached them, explaining that he was keen to begin a career in films and had been making them at home. They were interested, but wondered whether his preference for action movies was quite what was needed — Oli had been making films about the Swiss version of James Bond named James Tell, appropriately enough (we might print a few stills of Franco Frey, Secret Agent one day...). In the event, the London Film School advised that he was a little young to start a course, and he returned to Switzerland to begin his army service.

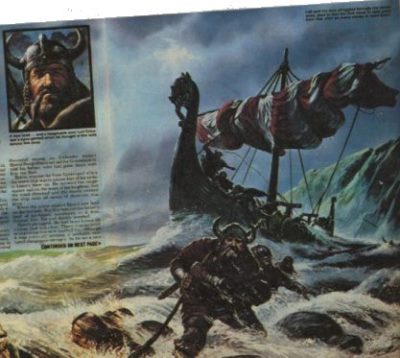

Double page marine illustration for Look and Learn, 1977

Plan B swung into action. At the time, the minimum period of national service in Switzerland was 3 months of basic training. Oliver decided to carry on for a while longer, and go for Corporal. After six months, his first spell in the army finished, and Plan C came to the fore — he started at Berne University, reading History, German Literature and English Literature with a vague view to entering the diplomatic service.

“Unfortunately, my university career wasn’t a roaring success,” Oli remembers, “I started going to the cinema seriously while I was at university, instead of going to lectures and it wasn’t long before I realised that I was much more interested in making films. After a term I left university and approached the London Film School again. I was accepted, and started a two year course in 1969. In those days it was called The London School of Film Technique, and the course covered all aspects of film making.”

And of course, while he was in London, Mr Frey had to support himself, to some extent, so he looked for some freelance comic work. “I went to the War Picture Library, who still publish war stories in comic-strip farm, and persuaded them to let me illustrate a story so I could show them what I could do. I was given a script and told to go away and draw a five page strip. They liked the work and I was commissioned to do a whole book — that took two months, working in a bedsit during the evening, and it was accepted.” Thus began a long association with the War Picture Library, which resulted in dozens of covers and illustrated stories.

At the end of the Film course, another period of compulsory army service in Switzerland followed, during which Oliver was given the chance to go to Officer School, and could have embarked on an army career. By now he had made up his mind. Neither the Diplomatic Service nor the Armed Forces tempted him — he was thoroughly hooked on films. So when he finished his army service, he returned to England to continue with his freelance illustration while he wrote a film script.

Returning to England, Oli looked up a friend from Film School days — one Roger Kean — and together they came up with the notion of setting up an industrial film company in Switzerland. The film script came to nothing, and Messrs Kean and Frey went to Switzerland with 16mm camera and professional sound equipment to make their fortune producing films for companies. “Unfortunately I’ve never been very good at selling,” Oil explained, “and Roger, while being more of a salesman, was hampered by the fact that he couldn’t speak German.” The film company gradually petered out, and Roger and Oliver returned to England.

Book jacket illustration for the Hamlyn Book of Horror, 1977

While he was in Switzerland, tying to sell the services of the film company to Swiss businesses, Oli continued to draw War Picture Library material on a freelance basis. Returning to England, he found an agent who specialised in comics, and a wide variety of freelance illustration work began to come Oli’s way. (Mr Kean disappears from the story for a few years, scampering off into the distance and becoming a film editor with the BBC, finally going freelance before being roped into the CRASH Editorship some years later).

IPC comics soon became a regular source of work for Oli. He finally caught up with his childhood heroes: for a couple of years he took over from Don Lawrence and drew The Trigan Empire for Look and Learn (before the novelty wore so thin that he had to stop or crack up), as well as general feature illustrations; then his interest in Dan Dare came full circle. He found himself drawing the very same strips as the artists he had admired as a lad!

Throughout the late seventies and early eighties Oliver established himself as a freelance comic artist — but other fields also opened up. Apart from regular work for IPC and the War Picture Library, Oli produced book covers for Souvenir Press, Video covers, and illustrations for children’s books, including Oxford University Press. More than a few history books (and the odd horror story compilation) have been graced with Oli’s work.

Oliver’s work was reaching a large audience — but one piece of work in particular reached a massive circulation... Oli had been seeking to diversify, and move gently away from comic work. Having heard that there might be a vacancy for a storyboard artist at Pinewood Studios, working on Superman, The Movie, he drove to the studios and met the Art Director. At the time, they were re-working the flying sequences, and while the Art Director was impressed with the Frey portfolio, he couldn’t afford the time to teach him about the technicalities of camera lenses and the like needed for this particular very specialist vacancy. It was no job.

A Dan Dare spread from an Eagle Holiday Special done for IPC Magazines in 1984.

Then, a week later, the Superman Art Director called Oli. They needed a 1930’s style Superman comic for the title sequences. Thus Oli found himself in an anteroom to the Director’s office, waiting for a couple of hours while a landslide scene was argued about, and discussed endlessly. Suddenly, the Director realised that someone had been waiting for hours to see him, ushered Oli in, explained what they wanted and asked for some pencil roughs of a 1930’s street scene “perhaps with a policeman swinging his nightstick....” A couple of days later, Oliver returned with a pencil rough of the strip and a comic cover inked in: “In the 30’s, Superman was drawn in a very rough style,” he explained, “and I was worried that I might let myself down by copying the rough appearance of the originals, so I inked in the cover and held my breath while I handed the work over.”

He needn’t have worried. The Director was well impressed and the rough of the cover was accepted on the spot and was used in the title sequence along with the finished version of the strip.

The Oliver Frey story moves, with him, to Ludlow in 1982. In the late seventies Oliver had visited Ludlow several times — long enough to fall in love with the town. It just so happened that the rest of the Frey family were looking to move from the Home Counties, and in 1982 an exodus to Ludlow took place. Franco, who’d gained a degree in Engineering since playing James Tell, and had been working on a variety of high-tech engineering projects, got involved with a German company which wanted to import Spectrum software from England. Franco bought a Spectrum and was busily playtesting games, researching the market for his German contact, when he came up with the idea of starting a magazine — or at the very least, a mail order service selling Spectrum Software. So it was all his fault.

In July 1983 the first mail order advertisement for CRASH MICRO GAMES ACTION was placed in Personal Computer Games, and Oliver was embroiled in producing illustrations for the catalogue... as well as publicity stills. Mr Kean was roped in, and somehow, the whole thing grew into CRASH Magazine, and Newsfield Publications.... The freelance work came to an end.

Most of Oli’s colour work for the magazines is executed using an airbrush to paint in large areas of colour, and backgrounds, with details being added with pen or brush. “I like the airbrush because it is simple, and is a very quick method of applying colour and adding effects. It’s a time saver. I remember one painting I did for Look and Learn, in which the foremast of a ship is shrouded in mist. All I had to do was paint the mast and rigging in solid black and then airbrush colour over it to give the effect of mist. If I had attempted that part of the painting using ordinary brushes it could have taken several days to achieve the effect I wanted, rather than a couple of hours. And time is of the essence, when you’re working as an illustrator.”

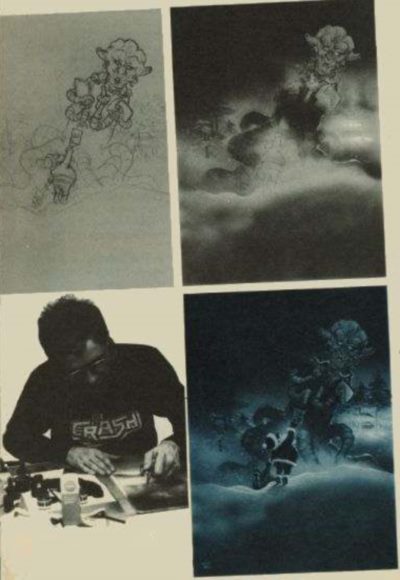

Several stages showing the development of this issue’s CRASH cover as Oliver works it up to completion

Oli’s only been using an airbrush for five or six years though. Most of his comic work was created using traditional brush and pen techniques, using acrylics. “It’s easy to overpaint with acrylics, and you have to be more careful in the planning stage when you’re using inks and an airbrush — it’s easy to lose the depth of colour if you try to put ink on top of another colour. Generally, I’ll produce a pencil rough onto the board I’m working on, and then spray the background and large areas of colour on top, adding the fine detail by hand.”

It took quite a while to convince Oliver that an airbrush would be useful — he remained convinced that far too much time would be spent masking off areas, applying a colour, removing the masking and then applying another mask for the next colour and so on which is the ‘classical’ way of working with an airbrush. Finally, he was persuaded to get a Thayer and Chandler airbrush after he had seen Terry Gilliam’s effortless use of airbrush technology. “I’m not very good at coping with technical things, and equipment,” Oliver confesses freely. Which is why he can often be spotted prodding his airbrush, looking puzzled, after it has clogged up — which it has a habit of doing every so often, despite the fact he uses special non-clogging American inks. “They’re strange things, these Luma Inks,” Oli explains, “you’re supposed to keep them in a cupboard locked away from the light. And whenever I’m spraying an orange background everyone tends to leave the Artroom — it smells disgusting, like someone’s been sick.” Which all goes to show what Oli’s prepared to go through to produce his paintings!

Given his background in comic strips in combination with his interest in films, it would seem logical for Oli to get involved with animated movies — perhaps involving computers. “I’ve never been tempted to get involved with computer art — I’m not really very patient. I find it difficult enough coping with the airbrush, which I like because of its simplicity; and I couldn’t sit down in front of a computer and fiddle endlessly with the keyboard to produce the result I wanted.

“When it comes to animation, there’s so much work involved that I’m sure I couldn’t put up with it. I’ve looked at the process, and gave up the idea of making cartoon films before stalling. So much of the work is mechanical, tracing hundreds and hundreds of cells and inking them all in — I simply wouldn’t be able to apply myself to such a task. Though if I had a team of animators at my disposal, to do all the finicky work....”

It’s not difficult to spot the influence Oli’s background in comic strip illustration has had on the overall look of the magazines — bold images zooming out of the pages are fairly typical of the design, which is the way comic illustrations work, picking on particular elements and emphasising them. “I became an illustrator in the first place because I liked comics, I’ve always liked comics,” he explains, “and this carries over into other areas of work.” Comics are fairly firmly ingrained on his consciousness nowadays!

‘When you’re working on a comic strip you tend to be illustrating stories provided for you by a writer — you work as a team. A good comic strip author has to realise what is and isn’t possible visually, and it can get very tricky, working as an illustrator, when someone who hasn’t such a strong sense of what is possible demands a very specific drawing.

By the time CRASH starter [...?] each illustration — which means he has to come up with ideas as well as paintings. He’s still producing pieces of work to suit a particular purpose, but he has more control over the whole process than he would have as a freelance.

Nearly all his paintings have a theme set in the past or the future — including the pure fantasy illustrations. Where does the inspiration come from? “I’ve never really liked the Here And Now — the Now doesn’t really inspire me. I’ve always liked historical things. All my paintings are bigger than life, mainly because life isn’t as exciting as it appears in pictures. I escape into a picture when I’m painting. When I’m really concentrating I sort of imagine I’m really there, looking onto the action in the painting — otherwise it’s difficult to see the things in my mind’s eye. It can take a couple of hours for me to go away from a picture — when I finish I sometimes spend an hour just sitting in front of the painting, staring at it. I’m in an alternate reality, I suppose. To work, the picture has to be convincing to me, which means I have to get really involved in what’s happening.” Which accounts for some of the rather strange facial expressions that sometimes rest on Oli’s face when he’s drawing a monster, or an action sequence... he has been known suffer from facial cramp as a result of some pictures!

“I’ve always been a dreamer, a romantic if you like. Ever since the games I played as a child when I was The Famous War Hero, or The Brave Sheriff Dealing With The Baddie, I’ve been able to get totally immersed in a fantasy world. I’m very interested in history, and read a lot of history books for relaxation, imagining I’m there. History is about real people, and I enjoy illustrating scenes from history, even though it involves quite a lot of reference work for accuracy. In some ways it’s more pleasing to draw futuristic scenes and fantasy — the referencing isn’t a problem, in that I make it all up, and it’s just a matter of producing a painting that has its own accuracy and detail. It’s more pleasing to make fantasy real than represent reality accurately.

“What I’d really like to do is direct a film, I suppose,” Oli mused. “Film is the ultimate fantasy-fulfilling medium. The closest you can get to film in a printed way is a comic strip, and there are a lot of common elements. I’d still like to be the director, sitting above a massive battle sequence with thousands of extras all re-enacting a scene from history. I would really be there, in control of the ultimate fantasy...”