A look at the crash of Imagine Software as seen through the eyes of a film crew.

[This documentary is now on YouTube and also available as a transcript. Thanks to those who made this possible. Thanks also to Gary Arnott for making the “broken Imagine logo” image available in a version for use with this article. — Web Ed]

Depending on when you read this article, you may be about to see, have seen or maybe missed, a fascinating programme on BBC2 television (December 13th at 8.00pm) in the Commercial Breaks series about Imagine Software Limited. The Liverpool software giant crashed out during the summer after a life of a little over 18 months, during which time it produced more hype than any other software house before. The company appeared to bask in self-created publicity, much of which was very clever, and so it seems appropriate that its death should also have been as well recorded for posterity by the media it sought for its promotion, as had its successes in life. As things turned out, the BBC film crew got a rather different story to the one they had conceived but much of the material shot for Commercial Breaks cannot appear in the finished programme, because it falls outside the scope of the series format.

Roger Kean spoke to BBC director Paul Andersen as he was busy putting the finishing touches to the programme.

Early in the new year of 1984 BBC Television director Paul Andersen, who among other things was about to direct some of the programmes for the Commercial Breaks series, witnessed the enthusiasm surrounding some of the new generation of computer games that were beginning to appear in the shops, and appreciated that the emerging software houses were pioneering a new market. Commercial Breaks is a series which broadly examines the struggles of individuals and companies who are trying to ‘break’ a new product into the market place. To Andersen the new computer game software ‘moguls’ seemed like a good subject for a programme and he began researching, looking for a suitable company to feature.

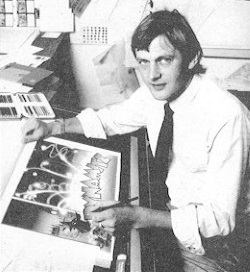

An obvious place to look was in computer magazines, and it rapidly became apparent that Imagine was a strong contender because of the spate of clever advertising that was then appearing which was designed for Imagine by Stephen Blower of Studio Sting, an offshoot company of Imagine, coupled with the fact that Andersen, like so many people in Britain, was reading the national press publicity about Imagine’s teenage programmer Eugene Evans, who was said to be earning £35,000 a year and could afford a fabulously expensive car when he was still too young to be able to drive it. There was obviously a story here for Commercial Breaks.

The next step was to approach Imagine and ask the owners whether they would mind being featured. So Andersen travailed to Liverpool and spoke to the young bosses of the new company, Mark Butler and David Lawson. Lawson had written Arcadia, Imagine’s biggest hit at the time, and Butler had sold it into shops starved of software over the 82 Christmas. At first they seemed a bit reluctant, and Imagine’s Operations Manager, Bruce Everiss, explained that there were too many things under wraps to allow in the prying eves of television. On the other hand the publicity-eager Everiss must have been able to see the promotional capital that could be made out of having BBC TV hanging around for some weeks making a film about them. Dave Lawson saw another angle altogether, and to appreciate this it’s worth remembering what put Liverpool on the map in the early sixties.

The Beatles transformed British (and then world) pop music in the early sixties, and created a modern myth about Liverpool, their home city. Over the years Liverpool has come to see itself as a possibly undernourished and underprivileged city, but one bursting at the seams with imagination and guts. With the eighties something similar to the Beatles seemed to be happening, only in computer software this time, and Dave Lawson must have seen Imagine as being at its very centre. Stephen Blower says that, ‘Lawson had some greater vision of what could be produced in software than anyone else I’ve ever met.’

At the time when Paul Andersen approached them, Imagine was working on the concept of the megagames, having exhausted the possibilities of the home computer’s limited memory. Lawson, who was largely responsible for overseeing their development, saw that the BBC would be able to record for posterity the concept, development and creative effort of a dedicated team in bringing these new super games out. In a way, the Imagine team, and especially the men who ran the company, would be seen to be ushering in a new Beatles era, but in software rather than in music. For the TV director the megagames also offered an essential linch pin on which to hang his programme. It all seemed ideal and, at the time neither party knew how dramatically different things would turn out.

When the BBC film crew went in to start shooting material for the programme they realised that Imagine made good visual material; huge, luxurious offices, acres of carpet, computer terminals by the ton load, lots of young programmers, secretaries in abundance, young ‘gophers’ acting as runners for the management and a company garage packed with a fleet of Ferrari Boxers, BMWs for the lesser executives and the famous Mark Butler custom hand-built Harris motorbike. At the time Imagine was employing 103 members of staff. Andersen had a funny feeling that it all looked too good to be true — and it was.

He noted that beneath the energy and bustle there were inconsistencies. Principal of these was an apparent split in the senior management which meant factions were working against each other. But the first noted discrepancy in the outward bravado was that Eugene Evans had obviously never received anything like the £35,000 a year quoted in the PR story. But what seemed more surprising to Andersen, was that Evans had never really written any programs either — certainly nothing that Imagine cared to publish. This might not have surprised some of his contemporary Liverpudlian programmers who were working for other software houses, however, who knew much better.

Eugene Evans, like Mark Butler had worked at Microdigital, one of the first ever British computer stores, situated in Liverpool. Bruce Everiss was also associated with Microdigital, and so were many of the programmers who were later to become the bedrock of the Liverpool software business. They all knew each other pretty well. It was the sort of in-bred atmosphere which leads to personality clashes, and soon enough the BBC team began to see evidence of them.

The disparity between the publicity hype and the reality became increasingly apparent during the summer months. Central to the problems was the fact that both Mark Butler and Dave Lawson had catapulted to fame and fortune within a few months. They would have been super-human if they had not come to believe a little in their own publicity and both in their different ways appear to have failed in coping with the fortune. Mark Butler’s background after leaving Microdigital was as Sales Manager for Bug-Byte where Lawson also worked as a programmer. They both left to set up Imagine in a small front room after several disagreements with the Bug-Byte management. The money that sales of Arcadia made over the Christmas of 82, was reinvested in bigger premises, personnel and in new programs, which also sold well. Naturally, the two young moguls needed staff and management to help administrate the in-pouring fortune, a classic situation which encourages the development of court chamberlains. One of the first such was Bruce Everiss, who seems to have naturally attached himself more to Mark than to Dave. Everiss was responsible for the day to day running of the company, but the responsibility for financial control and a directorship was put in the hands of Ian Hetherington. Hetherington attached himself to Lawson. The factions had begun.

One of Mark’s hobbies is fast motorbikes. He created the Imagine racing team and himself rode on the track. In fact Paul Andersen and the BBC crew were at the Isle of Man TT races in June filming at a time when Imagine was already in serious trouble and teetering on the brink of a crash. Mark did suffer a crash. Ironically, he was driven to the dismemberment of his empire swathed in bandages.

According to Andersen (a view backed up by many other observers), the two bosses thought that because of their success in the field of games production, it meant they could handle all sorts of other businesses as well. Almost at the outset they founded Studio Sting, together with Stephen Blower, the designer whose art work helped sell the company’s image and which adorned Imagine covers. Studio Sting was to act as a design centre and Advertising Agency for Imagine, which meant the company would be entitled to an discount on ad space booked in magazines. In return Stephen Blower received a 10% share of Imagine (which wasn’t worth all too much when the share was gladly handed over). Within a few months this situation had changed and the 10% was worth a lot on paper. The triad of Butler, Lawson and Hetherington wanted things rationalised — i.e. they wanted the 10% back. There are many rumours attached to the goings on at this time, in-fighting appears to have been rife, but whatever actually took place, the outcome was that Studio Sting was left holding huge magazine advertising debts (which have remained unpaid) but Stephen held onto his 10%, although he lost any executive post within Imagine. He therefore lost control over his own destiny when management decisions led to its downfall, and is still undergoing legal wrangles between himself and Butler/Lawson as to his financial responsibilities in the matter of Imagine’s vast debt.

In a telephone conversation with CRASH’s Kevin Foster, Blower said, ‘Imagine tried to accuse me of certain things that I didn’t do. For instance they said I was detrimental to the company’s image and that I was booking advertising space that wasn’t wanted. I was accused of stealing, or misappropriating £10,000, and my wife was accused of being incapable of keeping the books at Studio Sting. All this was later disproved in court.’

He went on to say, ‘They were obviously after my 10%. Imagine owed Studio Sting £89,000, so the way I see it is that they attempted to brush that debt under the carpet. The allegations were just an attempt to condone their own actions. I was probably the only one at Imagine who stuck to what he was best at doing.’

Late in 83 Imagine had set up a deal to produce games for publishers Marshall Cavendish which may have been worth as much as £11 million to Imagine. Early in 84 the contracts were signed, but even before Andersen had received the co-operation of Imagine to start shooting there were signs that all was not well with the deal. By the time the BBC crew was installed it was clear that things were going badly wrong. The megagames had intervened. Dave Lawson who, according to Bruce Everiss, always insisted that the programmers be left strictly alone, free to create without management interference, wanted to concentrate on the development of the megagames. Marshall Cavendish became disenchanted by the lack of progress on their games. They had already paid out a lot of money and seem to have been unhappy with the quality of what was ready. They pulled out and wanted their money back. But Imagine had taken on more people to cope, programmers, artists, musicians, gophers. None of these was laid off, the overheads went up alarmingly.

Meanwhile the megagames were not progressing as well as it was originally hoped they would. Andersen noted that John Gibson was working hard at Bandersnatch with Ian Weatherburn, but Psyclapse was nowhere, nothing more than a paper idea. Yet at this stage the artist Roger Dean (famous for his record album sleeves and mythological books) had already designed the boxes and the ads which were beginning to appear. Dean reputedly asked for £6,000 for this job, and Andersen thought he was ‘smart enough’ to have demanded it up front.

An important problem with the megagames was that they required a hardware add-on which was to be made in the East. To get the price right, enormous quantities would have to be manufactured. Imagine did not possess the money any more, and anyway could not have sensibly decided how many games would eventually sell. There was indecision all round. Bruce Everiss was to say later, ‘One option that we have is to sell the company as a whole to Sinclair Research, and I’ve been speaking to Sinclair Research, and they’re not interested. They’re saying that they want to keep programming of that nature outside their company.’

It transpired that Sinclair Research was only interested in buying finished product and that the megagames would have to be designed to work on the micro-drive, because they would not undertake the production of masses of hardware add-ons. In the event Sinclair Research did buy an option on Bandersnatch for the QL computer to go on micro-drive.

Another interesting rumour that Paul Andersen’s film team were able to verify, was what occurred over the Christmas period of 83. In 1982 there had been a software shortage in the shops. 1983 was to be a boom time, and Imagine decided on a clever ploy to foil the duplication of their rivals’ tapes. Ahead of time they booked the entire duplicating capacity of Kiltdale, one of the biggest duplicators for the software business. The idea, obviously, was to make it impossible for other major companies to get enough tapes duplicated for the Christmas rush. On paper it looked like an elegant piece of industrial sabotage. In practice it backfired. Imagine ended up hiring a warehouse for the storage of the hundreds of thousands of cassettes that they ended up with. After Christmas the bottom fell out of the market, and there was no way they could shift the games. This was a principal reason behind the strange move to lower the price of Imagine software. It also backfired because they flooded the shops with non-selling tapes, and then expected everyone to like the fact that the tapes would have to be sold at a price lower than the wholesale price the shopkeepers had bought the tapes in for in the first place.

So in the middle of shooting a TV programme about a company that was going places fast, Paul Andersen found himself filming one with a huge staff it no longer needed nor could afford, sitting on a vast stock of product it could not sell, with programmers left to their own devices much of the time and producing games that were increasingly unplayable and usually released with bugs still in them (remember Stonkers), run by a management team that was beginning to fall apart at the seams. Andersen recalls filming a meeting where the bosses sat around discussing how large the megagame boxes should be, whether they should be huge to entice punters to fork out £30 to £40, or whether the large size would put buyers off on the grounds that everyone knows model kit boxes are usually full of air. And this at a time when their empire was literally falling apart through lack of money and mounting debts. Lawson was buried in his megagames, Butler was acting out the role of playboy in his Ferrari and at the bike tracks. Everiss was trying to keep the offices running, while the rest of the ‘top management team’ struggled to cope with the increasing bitterness that was developing between the triad at the top. Some of the effects of what was happening were apparent to outsiders as well. I recall visiting Imagine for a meeting with Dave Lawson and Bruce Everiss sometime in late April. Lawson never turned up and Mark Butler appeared for a few moments, having just popped into the building to pick up some petty cash. It seemed a bit odd. The resulting article which appeared in CRASH naturally quoted Everiss the most. When the issue was published Butler rang me to complain that the emphasis was wrong — it made it sound like Everiss ran the company, he told me, when in fact he and Dave were still in charge.

As early as 16th April 1984, a petition was presented to the High Court by Cornhill Publications Ltd., to have Imagine Software Ltd. wound-up for non-payment of debts. At the time of writing I have been unable to establish what these debts were, or how they were incurred. The matter was ‘heard’ on the 11th June, three or four days before the TT races. On Monday 9th July at the High Court of Justice (Chancery Division) a further petition to wind-up Imagine on behalf of VNU Business Press (publishers of Personal Computer Games among others) went unopposed. Imagine was finished.

But what was happening back in Liverpool? The BBC crew were filming right up to the last moment, and witnessed the apathy and confusion that attended the last days. A memorable scene is the man from Kiltdale the duplicators, walking up and down Imagine’s offices trying to get to see either Butler, Lawson or Hetherington, the only people who could pay him the £60,000 owed by Imagine, much of it for the mass duplication done over Christmas in an attempt to prevent other software houses having games ready. He was in despair. But Mark Butler was not available, and the Lawson/Hetherington faction had disappeared.

According to Bruce Everiss they had already made their plans well beforehand, and events would appear to back him up. What he told Paul Andersen, is substantially the same as what he told me over the phone back in July. ‘I’m not a signatory on the bank, or anything, but I’ve had a look at the financial records of the company and there has never been a VAT return (Imagine had been running for 18 months and should therefore have made at least 6 VAT returns by law), never a bank conciliation, never a creditor’s ledger control account, never any budgeting, never any cash flow forecasting, no cost centres, not even an invoice authorisation procedure. Just no financial control at all.’

All these financial aspects were supposedly the responsibility of Ian Hetherington. Paul Andersen recalls that Hetherington was usually unapproachable during filming and had little if anything to say to the film crew.

Is it possible that Hetherington had already sussed out the true financial position of Imagine right at the start of his tenure? It would be odd if he hadn’t, since the cracks were there even before Christmas 83. What must surely have occurred to him is that Imagine was capable of making a lot of money, and that the megagames were going to make them all very rich. A lot of Imagine was now defunct and wasting money. Debts were getting to be astronomical, various attempts to raise money in the City had failed or been abandoned. If the company went, so would the investment in the megagames, so too would their personal finances.

Everiss again: ‘Dave has become anxious about losing his big house in Coldy and about his kids at expensive schools and Ian has become greedy and wants to become a millionaire overnight. So Ian has presented this Finchspeed plan to Dave. Dave, grasping at straws, has taken it on board — which means that only 20 people will be employed.’

Finchspeed. The name first hit the press after the Imagine collapse. Finchspeed was the new company founded by Dave Lawson and Ian Hetherington for what appears to be the express purpose of acquiring all the Imagine assets. As a result of canvassing opinion and currying favour with those programmers whom Lawson and Hetherington considered ‘sympathetic’ to them (rather than the Butler/Everiss faction), jobs were offered in the new company to approximately 20 people — in fact those needed to continue work on and complete the megagames.

At the time the Finchspeed documents were drawn up very few people knew about the Lawson/Hetherington plans. It seems Mark Butler had no idea and Bruce Everiss certainly didn’t. ‘They didn’t tell Mark about this until the very last minute when they let him in on a third of Finchspeed, ‘ Everiss told Paul Andersen later. It seems incredible that the duo thought they could get away with transferring assets from a company part-owned by Butler, without his knowledge. Stephen Blower was also in the dark. Later, he was to be held jointly responsible in law for Imagine’s debts. He told us, ‘I’m still liable for the overdraft, which was £112,000 at the last count. If it came to court I think I would have a good case against them, as has been shown last time I took them to court.’ Blower appears to have maintained that Butler and Lawson should have protected his interests better, and the Courts have agreed. Butler and Lawson were ordered to pay Blower back the £89,000, but failed to do so. At a later hearing the Judge said that he ought to send Butler and Lawson to jail, for refusing a court order to pay, but they were let off on the grounds that in jail they would be unable to put matters right and that it was in the best interests of both parties if they were allowed to continue their present work to be enabled to pay Blower.

Although the Finchspeed arrangements were made in secrecy, it did not quite escape the notice of the BBC 1 team, who actually filmed Dave Lawson signing a legal document relating to some aspect of Finchspeed. This shot appeared in the ‘rough cut’ of the programme (at the time of writing it is not known whether it remains), but because this deal was largely outside the scope of the programme, the shot is just there as visual background.

On a later occasion the film crew were also present when Dave Lawson’s wife came into his office to get papers signed for a passport shortly before he left for America with Hetherington. With the winding-up orders going through the courts unopposed, Lawson and Butler prepared to disappear from the scene.

On the telephone, Hetherington told us, ‘I didn’t run away anywhere. I spent four weeks, day and night writing a business report. I was in America for fund-raising, and we were damn near successful, but we had to have our trip cut short because of the goings-on at Imagine.’ He added, ‘I’m sick to death of people insinuating that anything untoward happened at Imagine.’

In retrospect it seems incredible that they should leave the country at such a time, unless one supposes that they felt unable to face the imminent disaster. Protests that the trip was a realistic fund-raising exercise for Imagine seem undermined in the face of the writs going unopposed through the courts before and during the trip. As soon as the two men had gone, numerous creditors, trying for weeks to get some reply to their demands for overdue payment, were stumped because with Lawson and Hetherington gone, there was no one able to cope with the financial problems. It’s hard to accept Hetherington’s comments to us at face value when (whether intended or not) his absence put a total block on payments. Yet equally it must have been clear to him that payments could not be met.

With knowledge that VNU had successfully issued a winding-up order on Imagine, the rest of the company’s creditors began jamming the switchboard to find out what was going on. CRASH was one of them. The official line was that things were quite normal. But no one knew where Lawson, Hetherington and Butler were. Everiss told Paul Andersen, ‘Mark didn’t know where they’d gone. The only person they told was Andrew Sinclair, who basically’s just David’s gopher, and Andrew has been spying on Mark and myself and reporting on a daily basis to them in San Francisco.’

One press mention did suggest that the two directors were in the States trying to raise venture capital in Silicon Chip Valley to save Imagine, but this would appear to be out of character with their recent actions in moving assets from Imagine to Finchspeed, and gives strength to Bruce Everiss who said, ‘All they’re trying to do is finance Finchspeed with capital from San Francisco.’

The significance of the passport signing became more apparent when it was realised that both men had taken their wives with them on the trip to America at a cost estimated by Everiss to be possibly as high as £10,000, and that at a time when creditors were crawling all over the building trying to get paid.

On the day Mark returned from the races, wrapped in bandages and driven by someone else, he arrived at Imagine headquarters to find the bailiffs were in. One of the items they impounded was his pride and joy, the Ferarri Boxer. Paul Andersen recalls that he seemed stunned and totally out of his depth. He didn’t know what to do or who to blame; it seemed he was genuinely unaware that things had reached such a state or that his co-directors had fled the country and were in hiding (as everyone said) incommunicado. So closely did the TV crew follow the proceedings that they almost had their camera gear locked into the building by the bailiffs!

Mark went off, to return two or three days later before the assembled staff and told them in a brief speech that it was over, that he hoped they would get paid what they were owed if it was possible, and that he would try to find alternative employment for as many as possible. During the period between Lawson and Hetherington vanishing and the bailiffs arriving, life in the Imagine HQ appears to have been as disorganised and dream-like as it was in Hitler’s Berlin bunker. In reply to Paul Andersen’s question about what had been happening, Everiss replied: ‘Well, there was a whole pile of people just playing games there and they’re hiding from the camera. If you go round the corner here, by the exit, you’ll find there’s a big pile of empty fire extinguishers because there’s been fire extinguisher fights all week. That’s been the main event.’

As far as the BBC team could see, the staff were mostly sitting around, watching videos and waiting for the end. Everiss was left with trying to find jobs for about 60 staff, those left behind by the new Finchspeed crew, and in the end he felt morally obliged to resign. ‘Dave and Ian, being too much of cowards to face up to me, have told Mark that they wouldn’t want me here when they returned,’ he said.

That was largely it for Imagine Software Limited, but not for the people involved. Finchspeed has gone on to develop the megagame Bandersnatch for Sinclair Research to bring out on the QL in the New Year, with a royalty from each unit sold going back to the Imagine liquidators to help pay back the company’s debts. It is a critical time for its directors, Dave Lawson and Ian Hetherington, who are naturally afraid of any adverse publicity. Even as I was in London seeing the rough cut of the TV programme, Ian Hetherington was on the phone trying to get hold of Paul Andersen. When I returned to Ludlow that Friday evening, I was greeted with a message that Hetherington had rung me to find out the same thing, having heard that we were writing about the story. Unfortunately for him he spoke to our Financial Director, and was told that as he still owed us £5,825, it wasn’t sound sense to bother us!

We phoned him on the following Monday morning, when he spoke to Kevin Foster and gave him the quotes used in this article. He also implied that if we printed anything he didn’t like, we would be making him a rich man. Implications of libel actions are all very well. The fact remains that CRASH along with other publications, had been promised payments by both Imagine’s promotional department and (in our case) by Hetherington personally. These never arrived. But at the time, he and Lawson were assigning assets out of Imagine into another company which they both part-owned at a time when Imagine was hopelessly in debt, and desperately required those assets if it was to have a hope of staying alive. Recognition of this fact can be seen in that a royalty on every copy of Bandersnatch sold by Sinclair will be going back to Imagine’s liquidators.

Some of the programmers are now working freelance on games for Ocean, and others including John Gibson have founded a new Liverpool company with partial backing from Ocean called Denton Designs and their first game, an adventure entitled Gift From the Gods should be released through Ocean shortly. Mark Butler is working with his father in another software company called Voyager. Stephen Blower worked for the year as a freelance and is now at Ocean, where he has recently been made a director. Of the collapse of Imagine he had this to say, ‘Through greed, or little boys playing at big business, or whatever it was that carried it all they ruined something that was worthwhile carrying on with.’

Hetherington added, ‘My attitude has always been that it’s all over now, and what we’ll do is quickly get our lives back together again. I don’t want people bringing back something that happened six or seven months ago. What we’re doing now, Dave and I, is improving on megagames to produce something quite startling. We want to bow out at the top.’

In summing up his unique experience in watching the death of the software giant BBC director Paul Andersen said, ‘It was a fascinating time in a city at the focus of the software business. It’s a shame it all fell apart — there were a lot of talented people there who were let down. It’s a bit like a movie that never got made, all the technicians and all the energy, but the producers failed. It’s going to be interesting to see what will come of them all.’

With the finish of Imagine the TV programme may have looked as though it was over too. However Ocean bought a major portion of Imagine’s assets and so Paul Andersen had a finale thrown in his lap. Filming continued at Ocean’s offices in Manchester, as they worked on Hunchback II. The BBC may not have got the story of the Imagine megagames, but at least they managed to follow the development of computer games from concept to release, and in the process they saw a fascinating slice of corporate life.